Public health researchers have called food allergies “a growing public health epidemic in Canada” affecting around one in 13 Canadians and one in five Canadian households. Dining out can be risky and stressful for people with allergies, in part because many restaurant employees lack the training, skills and confidence to manage food allergies safely and effectively.

These are challenges that existed before the COVID-19 pandemic and will surely persist after it. In recent years, news outlets across Canada have reported several cases of people suffering extreme, sometimes fatal, allergic reactions to restaurant food. Accidents like these are most often due to miscommunication.

As researchers in the field of industrial-organizational psychology, we analyzed how and why information about food allergies gets communicated, and miscommunicated, at restaurants. We approached allergy communication the way we might approach communication among a flight crew or a surgical team: by isolating the make-or-break behaviours in the communication process.

Based on this research, we offer some guidelines to reduce the risk of allergic reactions at restaurants and improve the customer experience.

Table of Contents

Allergy communication

(Shutterstock)

Allergy information can be communicated in written and verbal forms. Written communication happens on a restaurant’s website, posters in dining rooms, menus and ingredient lists. It also happens among staff, such as on order forms and point-of-sale (POS) machines.

Still, most food orders involve verbal conversations between customers and servers. In these conversations, customers and servers get a sense of one another and decide together how best to manage the customer’s food order.

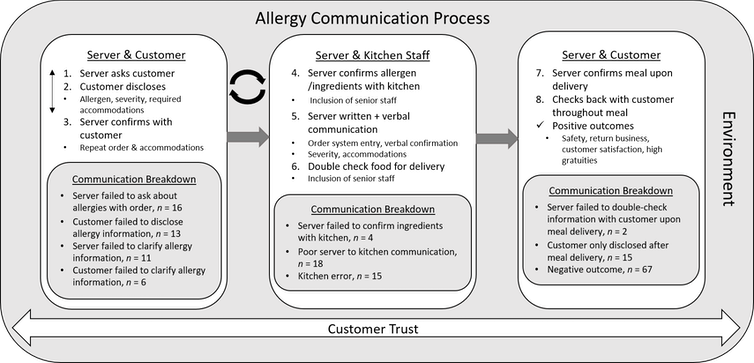

We collected examples, or critical incidents, of restaurant staff handling a food order for an allergic customer. We received 107 successful incidents and 61 failed incidents from a variety of restaurants. Failed incidents involved things like an allergic reaction, staff having to remake a meal and/or an upset customer.

For each incident, staff reported who was involved, what went right, what went wrong and how. Based on these, we mapped the process of allergy communication, from customer to server to kitchen staff and back, and pinpointed where mistakes commonly happen, as illustrated in this diagram.

Reprinted from International Journal of Hospitality Management, DOI: 10.1016/j.ijhm.2021.102959, with permission from Elsevier., Author provided

Aside from these incidents, we also asked 138 people with moderate-to-severe food allergies to describe their own encounters dining at restaurants.

As you can see, communication at restaurants works like a game of telephone, where messages pass from customers to servers to kitchen staff. As in telephone, mistakes can happen at any stage, and given enough time, mistakes are bound to happen. Unlike telephone, though, mistakes can be anticipated, avoided or fixed.

Recommendation #1: Ask about allergies

Most miscommunications happen when customers forget or are too shy to disclose their allergy. We suggest that servers ask customers to disclose their allergies when introducing themselves: “Hello, my name is Sam and I’ll be your server. First off, does anyone at the table have food allergies?”

To be clear, we are not suggesting that allergy disclosure is the server’s responsibility. Quite the opposite: most people we asked (staff and customers alike) agreed that disclosing allergies is primarily the customer’s responsibility.

We suggest that servers ask customers about allergies simply because that’s the most effective approach. A typical server deals with far more food orders than a typical customer. So, staff may not only be more apt to develop the habit of starting conversations about food allergies, trained servers have the opportunity to lead the conversation.

In the same interaction, some customers mention their allergy but leave out important information, like how serious the allergy is. According to staff we surveyed, customers should not just state their allergy; they should also describe the severity of the allergy.

Recommendation #2: Double-check

Staff and customers can integrate double-checks to catch and reverse miscommunication before it leads to disaster. Double-checking involves repeating information back to the speaker and asking for confirmation. For example, when a customer discloses an allergy, the server can repeat the allergy and accommodations back to the customer, and ask the customer to confirm that this information is correct. In the diagram above, we highlighted four points where double-checking is most helpful.

Of course, it might not be realistic to include double-checks at all of these points. Still, each additional double-check could improve your chances of catching an error and saving a life.

Recommendation #3: Involve fewer staff

Again, the allergy communication process works kind of like a game of telephone, and telephone is easier with fewer people playing. In the same way, it can be helpful to reduce the number of people that have to pass along a message. Restaurants that do this well often designate a staff member, manager or chef to directly oversee orders for allergic customers.

No one likes fakers

Both allergic customers and staff raised the problem of allergy “fakers” — people who claim a food allergy that is really just a preference. These fakers aren’t just annoying. They muddy the waters of allergy communication, making it more difficult for customers and staff to trust one another. This is one more reason that customers need to be clear about the severity of their allergy, and for staff to treat all allergies seriously, even when in doubt.

Many restaurants already follow some or all of these recommendations, but many don’t. Every restaurant, every staff member and every customer is different, so these recommendations are meant as a suggested starting point. We kept our recommendations simple so that they’re easy to adopt or adapt.

Good habits can reduce allergic reactions, improve customer experience and strengthen staff confidence to manage allergies. What’s more, people with allergies can be loyal customers to restaurants they consider safe.

![]()

Timothy Wingate has received funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Joshua Bourdage receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

Samantha Jones receives funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council.

Malika Khakhar does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.