The three-year anniversary of the legalization of recreational, or non-medical, cannabis in Canada arrives on Oct. 17. It also marks the start of the government of Canada’s mandated review of its health impacts.

Unfortunately, the slow roll-out of Canada’s cannabis retail market combined with the glacial speed of academic research means everything you and the government will be hearing about the health effects of legalization is based on outdated and often irrelevant data.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Jonathan Hayward

There are three key limitations of our understanding of legalization’s health impact.

First, almost all studies to date examining the impact of legalization on cannabis use and harms have only looked at changes during the first year following legalization.

Yes, these results are reassuring: small increases in cannabis use across Canada, and modest or no increases in ER visits or hospitalizations due to cannabis in Ontario, Alberta and Québec. However, we need to keep in mind that the transition from cannabis being illegal to being widely available for legal purchase and use is not a switch that was flipped overnight.

Remember, Ontario did not have a single legal cannabis store for the first six months after legalization, Québec had just 14 and the rest of the country didn’t do much better. The limited stores that were open often didn’t have much cannabis to sell due to major product shortages.

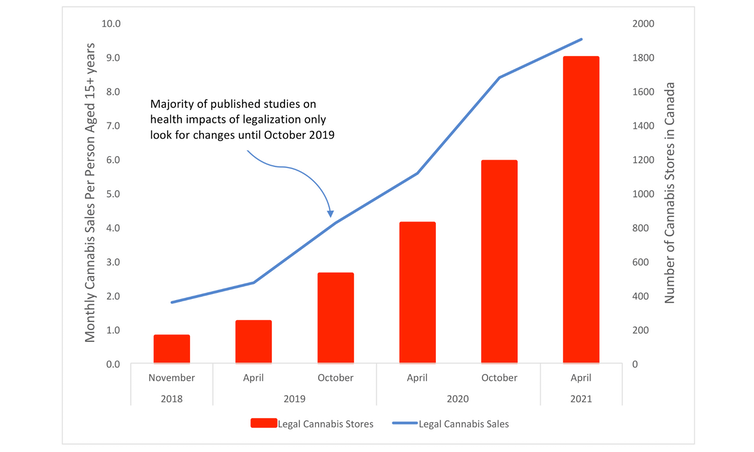

But the cannabis retail market looks very different today. I lead a team that has tracked the enormous growth in the number of cannabis stores since legalization. Our current data show more than a 10-fold increase in stores between November 2018 and April 2021 (from 158 to 1,792).

During the same time, Canadians increased the amount they spend a month on legal cannabis by 428 per cent, to $9.50 per person aged 15 and older from $1.80. Ontario currently has so many authorized cannabis stores — 1,175 of them — that experts predict major store closures.

(Daniel Myran), Author provided

Data from Statistics Canada suggest that the maturing market may be starting to impact overall cannabis use. For the first year-and-half post-legalization, the legal market expansion essentially matched illegal market contraction. However, since early 2020, increases in legal sales have dramatically outpaced decreases in illegal sales, resulting in increased overall spending.

(Daniel Myran), Author provided

Second, many types of cannabis products, including commercially produced edibles such as THC-containing candies, desserts and drinks, only became available for sale in January 2020. These types of products have been implicated in large increases in cannabis poisonings in young children in the United States. One study in Alberta reported increases in cannabis poisonings in children following legalization. However, the study did not examine the time period after commercial edibles were introduced — the exact time we would expect the biggest increases, based on the U.S. experience.

THE CANADIAN PRESS Jonathan Hayward

So while current studies support that there was no increase in harms in the initial months of a heavily restricted and limited retail market, we have almost no data on the health impacts of our current, far more mature, cannabis market.

The little that we know is concerning. While the number of people who use cannabis almost every day in Canada didn’t increase much immediately after legalization, by late 2020 it was up 46 per cent (5.4 per cent in early 2018, 6.1 per cent in early 2019, and 7.9 per cent in late 2020).

An estimated 16.3 per cent of Canadians aged 18-24 years now report near daily cannabis use, an increase of 65 per cent since legalization. Emergency department visits and hospitalizations due to cannabis in Canada are also up eight per cent and five per cent respectively, between 2019 and 2020.

Which brings us to the third limitation. For anyone thinking, “Hold on, what about the COVID-19 pandemic?” you’re right, it’s a major problem. Over half of the time since legalization has been during the pandemic.

There is no easy way to separate the effects of the pandemic versus a maturing cannabis market on the recent increases in cannabis use. More data is coming — the federal government has invested millions of dollars in research — but we will need to wait to see those results.

The legalization of recreational cannabis, which has resulted in major reductions in social harms such as heavily discriminatory police charges for cannabis offences, has had major public health benefits.

THE CANADIAN PRESS/Tijana Martin

My concern is that an increasingly commercialized cannabis market may lead to increases in cannabis use and harms. Groups with financial interests in selling cannabis are already claiming that current regulations such as cannabis taxes, child-resistant packaging and restrictions on cannabis advertising including on social media, are restricting innovation. They argue these must be updated — meaning removed or reduced — to compete with the illicit market.

During the upcoming regulatory review we need to remember these regulations were thoughtfully put in place. Decades of alcohol and tobacco research, and emerging cannabis-specific evidence, suggest these measures are highly effective at reducing cannabis use in youth and young adults.

The federal government recommends that people start low and go slow to avoid potential adverse effects from cannabis. The rapid expansion of the cannabis retail market over the last year is the regulatory equivalent of our country having ingested a very large cannabis edible for the first time. We have no idea how high we are about to get. While we wait to find out it probably is not a great idea to have another edible.

My advice to the government during the upcoming review is to listen to their own recommendations and go slow on any changes in cannabis regulations.

![]()

Daniel Myran receives research funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the University of Ottawa Department of Family Medicine and is based at the Ottawa Hospital Research Institute. The views presented are his own and not necessarily representative of his affiliated organizations.