Jan Huber/Unsplash, FAL

As I walked her up the flight of stairs to my clinic room, Victoria* barely engaged with my small talk. I glanced back at her. Above her mask, she looked strained, miserable, and I saw that her reticence was because she was ready to burst into tears. I thought one more question might have tipped her over the edge, so we continued in silence until we reached the sanctuary of the outpatient room.

The tears were not long in coming. She told me that early in the pandemic, before COVID testing was widely available, she’d had what was assumed to be a mild case of the illness. Her doctor advised her to stay at home, which was the standard advice to everyone at that early stage of the pandemic. For the next few days, she lay in bed. A week passed, then two, and then steadily the weeks turned to months.

“I had long COVID before it had a name,” she told me. Yet even after it had a name, even after she had been assessed, X-rayed, had an MRI and countless blood tests, she was little better off. And even once people started talking about it, the name “long COVID” offered no clues about how this illness was to be treated, how long it might last, or what the future would now hold for those with it. And so at each clinic appointment – “Good news! Your lung function tests are completely normal!” – Victoria began to feel more adrift. If they couldn’t find anything wrong with her, how was this ever going to be fixed?

This is a scenario that I have frequently seen over a long career working at the interface between mind and body: a place where the clean lines of diagnosis blur into the shades of grey that constitute the real world. It is an area in which medicine struggles to make sense of a person’s suffering, where patients feel neglected and abandoned, and where opinion replaces evidence. Instead of a cohesive pull towards a solution, there is confusion, uncertainty and fragmentation.

The treatment of any illness starts with a conceptualisation of the symptoms. What is causing the problem? Where are its origins? Our ability to peer into the body, to examine its organs and measure and make sense of the invisible elements in our blood, have persuaded us that illness is nothing more and nothing less than a bit of the body having gone awry.

Yet Victoria’s body had not gone wrong, at least not in any way that was apparent to the increasing number of medical specialists who had examined and investigated her. What did that say about her suffering? She began to doubt herself, as surely as she knew her family was beginning to wonder, too.

Table of Contents

Medical purgatory

Stories like Victoria’s aren’t uncommon among the thousands of cases I have seen over the years. Not all of my patients have had long COVID, of course, but many have had one of the number of hard to define illnesses, where a person’s suffering isn’t accompanied by any abnormal test results. They inhabit that flat grey hinterland, neither one thing nor another.

My own journey to this point involved a steadily increasing understanding that medicine often does not serve patients like Victoria well. Patients referred to me had often seen several teams of hospital specialists with problems such as persistent pain, fatigue, dizziness, unexplained abdominal symptoms and seizures that were shown not to be epileptic. Following the law of diminishing returns, each round of investigations brought smaller and smaller yields, until a referral to a hospital psychiatrist became the only card left to play.

This story is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism and is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects to tackle societal and scientific challenges.

A dawning realisation that things had to change struck me from early on in my career. Back then, even as a sprightly junior doctor specialising in internal medicine, I could not help noticing that many patients did not benefit from medicine as it was being practised. And so I found myself wondering if I could do more good as a psychiatrist than as a physician in a general hospital.

Eventually, I worked my way up the career ladder, specialising in the interface between medicine and mind – a field known as liaison psychiatry. More recently, I have written about my experiences of how the mind and the body are inextricably connected in a book.

I remember seeing Finlay*, a young man whose life was put on hold after he went to see his doctor complaining of dizziness. Over the following months, he was passed around different specialist departments including cardiology, ENT (ears, nose and throat) and neurology. He was subjected to dozens of investigations, all of which came back normal. He was no longer sure if he was really ill, and found it hard to make sense of his situation. His employers started to lose patience with him, and his relationship with his partner came under strain. The doctors had moved on, but Finlay was stuck. He was frustrated, scared and still dizzy, and like his referring doctors, just wanted an explanation for his symptoms that made sense.

I have lost count of the number of times a patient has wished on themselves a serious illness, even one with a poor prognosis, as long as it has clear investigative results. At least they would then be able to justify their suffering and plan for the future.

The problem is one of culture. Western culture has become so steeped in its current thinking of the human body – a simplistic mechanistic approach – that to suggest physical symptoms may not always have a direct physical correlate in the body is, for many patients, a provocation and, for doctors, something that is often not considered.

Wellcome Collection

In some respects, this is surprising, because western culture likes to think of itself as more open, inclusive and accepting of things that fall outside the conventional paradigm. Yet this openness does not often extend to healthcare, in which medicine’s narrow view of health and illness continues to constrain its thinking.

When a doctor is unable to find a clear-cut physical cause for a patient’s illness, many will hear in this that their symptoms are not quite real, their suffering suspect. Doctors can become reluctant to even suggest that physical symptoms may not have an obvious or demonstrable physical cause, for fear of the offence that it seems to imply. One 2002 research paper, published in the BMJ, encapsulated the difficulties in the title: “What should we say to patients with symptoms unexplained by disease? The ‘number needed to offend’.”

Everything must make sense

The west’s present medical culture is a continuation of a process that began in antiquity. It is a reflection of human nature, the need to try to find order in the world, to delineate a set of rules, so that the world around us makes sense. It gives us a feeling of security. We want to explain and contain those things that frighten us, such as ill health. This, in turn, leads to a drive to simplify complex phenomena.

In some scientific disciplines, simplifying to a set of fundamental rules is a perfectly legitimate goal. By doing so, we have understood the relationship between energy, mass and the speed of light, the structure of atoms, and much of the physical world around us. But in medicine, the urge to simplify has nearly always led to overly simplistic theories. These theories explain everything and nothing at the same time.

Take, for example, the four humours theory of medicine. It began in ancient Greek times when Hippocrates and then Galen developed the idea which, almost unbelievably, became the leading medical theory for the next two millennia, with barely a challenge to its legitimacy. It explained everything.

Misalignment of the four humours – black bile, yellow bile, phlegm and blood – needed to be corrected to ensure good health, and so poultices, emetics, blood lettings and a variety of other benign, and not so benign, treatments were developed. It was a unifying theory, at once elegant, simple and persuasive. Its power was reflected in its longevity. And yet it explained nothing at all. It was nonsense accepted as truth.

Wellcome Collection, CC BY-NC

Our urge to simplify the complex has remained unchanged in modern times. It is only the parameters that have changed.

The current conceit is of the body as a machine. A complex machine, for sure, and one that needs a great deal of scientific effort to explain its workings. We have made substantial progress over the past half century, with a deeper understanding of the workings of the body, from microscopic cellular function to nerve cell transmission, from microbiomes to genomics. It has allowed us to understand disease processes and offer treatments that could not have been conceived of a century ago. Treatments like dialysis, which has extended countless lives, and organ transplants, which have been made possible by our understanding of the immune system to prevent rejection.

Such achievements have been an undoubted benefit to many people, and are obviously to be welcomed. Yet the understanding of the body has not translated into an understanding of illness and health. There is a ghost in the machine. Health, as experienced, is not simply a reflection of whether our bodily machine is working as it should. For many patient encounters, it’s not even close.

This is reflected in the many examples that we experience on a daily basis. We know for example that depression commonly presents with physical symptoms, such as headache or constipation, a finding that appears to be consistent across different cultures. Similarly, it is well known that placebos can improve physical symptoms – in one study improving lower back pain even when the subjects were told that they were taking an inactive placebo tablet.

The case of psychiatry

As the west’s current model of medicine became the global standard, it began to shape the way we thought about and treated physical health problems. The potential contribution of psychiatry to physical health problems in the UK was little considered before the 1950s, with the speciality of liaison psychiatry developing in the second half of the 20th century. Even now, nearly all psychiatry is practised in the community or specialist psychiatric hospitals, rather than in acute medical settings.

In the general hospital, psychiatry is mostly to be found in the emergency department, with the focus firmly on self-harm, suicide attempts and extreme psychological distress. This means that where patients have medically unexplained symptoms, or long-term medical conditions in need of psychological care, psychiatry is often not around to help manage them.

Yet there is an ongoing need for psychiatry to address problems such as unexplained seizures or tremors, pain that persists despite a lack of any objective disease, the assessment of patients refusing life-saving treatments, and the many other problems that can have less obvious presentations, such as the long-term effects of abuse presenting with urological symptoms. All of the hospital specialities end up interacting with a good liaison psychiatry service, if it is available.

But even if psychological support is available, the problems do not end there.

For illnesses like heart disease, psychological support (for example, to improve stress management and help address mood and anxiety-related exacerbations of symptoms) is generally accepted, because the bona fides of the diagnosis are not brought into question.

Yet for illnesses like Victoria’s, where the physical basis of the diagnosis remains unclear or unknown, experience tells us that a psychological approach implies for many patients that the illness is not being taken seriously. If there is no demonstrable physical cause, then any non-medical treatment is seen as suspect, dismissive of the physical, and an implied trivialising of suffering. Western medicine has become trapped in a simplistic and one-dimensional view of illness.

Ani Kolleshi/Unsplash, FAL

The consequences of this current medical approach are unsustainable – and the statistics speak for themselves. Consider this: one large 1989 study in the US showed that doctors found an underlying physical cause in just 16% of cases of common symptoms, such as fatigue, dizziness, chest pain, back pain or insomnia. This is a jaw-dropping figure, almost hard to fathom, although typical of a number of studies over the 30 years since that have produced similar results in diverse settings.

In one study in London, no medical explanation accounted for 66% of patient encounters in a gynaecology clinic. In the Netherlands, just under half of all hospital medical encounters had a definite medical diagnosis to account for the patients’ symptoms. For a large number of symptoms that people see their doctor for, “no medical cause” is one of the most common, if not most common, finding for the patient’s symptoms. This is true in both primary care as well as secondary care at the hospital.

The costs of this to the NHS are eye watering. It is estimated by the King’s Fund that at least £11 billion each year is spent on poor management of medically unexplained symptoms as well as the consequences of untreated mental health conditions among those with long term health conditions.

Yet the money is far from the worst of it. It is the human costs that are the real story. Added to the protracted ill health and disability are unemployment, financial adversity, strain on relationships and an overall reduction in quality of life.

Looking beyond

Psychiatry and psychology can make a meaningful difference to patient outcomes, although they are rarely invited to do so, and there is commonly little will or resource to fund such services in any case.

This is now a real cause for concern around long COVID. We are still finding our way towards explaining what exactly this illness is. It appears to encompass a range of conditions. There are some cases showing demonstrable pathology, with abnormal blood tests and imaging, and many, like Victoria’s, which do not.

This may be because our understanding of how the body develops and perceives symptoms has its limits. But the patient’s suffering is very real, whether or not a physical cause can be shown. Whatever the cause, we know that depression, anxiety, fatigue and insomnia frequently accompany a chronic and often disabling illness. We also know that there is often no association between the severity of the original infection and the subsequent long-term disability: people with initially mild infections can suffer long-term effects.

Without addressing these issues, offering practical rehabilitation and physiotherapy, and addressing the fear and despair that patients experience when facing a poorly defined but seemingly chronic health problem, we can make the patient’s situation worse.

The starting point of any successful treatment has to be a shared understanding of the nature of the problem. We need to have an open conversation in society about the mind and body, health and illness. We need to be realistic about our current understanding of the body, celebrating the truly impressive treatments and innovations that the past half a century of medicine has brought us, and honest about the limitations.

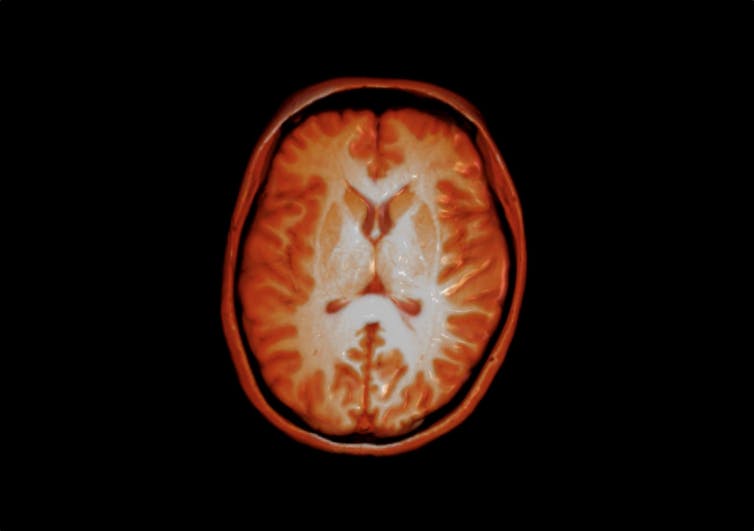

© Dr Flavio Dell’Acqua, CC BY

For Victoria, the hardest part of her treatment was managing her doubt and uncertainty about what was wrong with her. After months of normal investigations and an increasing sense of feeling like she was being told that she was “not really ill”, she needed some validation of her illness –- to know that doctors believed in it. It says something about our current medical system that this needs to be said at all. Of course she was ill, just probably not within the narrow construct of illness that we currently employ.

It is possible that, one day, we will discover all of the physiological processes that go wrong, and the huge number of currently unexplained illnesses will have demonstrable abnormalities to find and benefit from crisp, targeted physical treatments. I hope so. It is a worthy – albeit, in my view, unlikely – goal.

Yet this still disregards the psychological components that all illnesses have. All illnesses have a perceptual and psychosocial component, which is to say that our experience of symptoms can be very subjective and influenced by a variety of non-medical factors. It is well known that experience of pain is influenced by our expectations, how serious we think the cause might be, our culture, our mood, even the language we use to describe pain. By addressing all these factors, psychological approaches can reduce and even cure symptoms.

When assessing a patient with medically unexplained but persistent physical symptoms, a psychiatrist needs to explore all these other factors that could be important in ameliorating the symptoms. This includes identifying any current mood disorders, such as depression, as well as anxiety disorders, which may be maintaining or exacerbating the problems. Focusing on the symptoms is an understandable but unhelpful means of perpetuating problems. This is often driven by fear of what the symptoms may represent, so an understanding of the person’s views on the illness, how serious they believe it is, whether they believe it to be controllable or not. All these are all important to elicit and address.

Psychological approaches are not meant to replace medical care, any more than they would replace insulin therapy in diabetes or cardiac drugs for heart disease. But they can complement that care. Their use is not meant to suggest the patient’s symptoms are not real, nor imply they may not have a real, physical basis.

Yet this debate has been going on for so long that I am not sure if medicine can rise to the challenge. The insatiable demand for spending on health and the relatively low priority of psychiatry, mean that outside of a few bigger centres, the kind of specialist, integrated treatments needed are not commonly available.

With an estimated 2.3% of long COVID patients having symptoms beyond 12 weeks, how long can we keep mind and body separate? We have had centuries of a mind-body split. Perhaps helping to bridge this divide will be COVID’s next surprise.

* Names and patient details have been changed to protect patients’ anonymity.

For you: more from our Insights series:

-

Drugs, robots and the pursuit of pleasure – why experts are worried about AIs becoming addicts

-

Loneliness, loss and regret: what getting old really feels like – new study

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

![]()

Alastair Santhouse is the author of Head First: A Psychiatrist's Stories of Mind and Body.