The NHS is going through the worst winter crisis since records began, with waiting times for ambulances, in A&E departments and for elective surgery all longer than ever, leaving thousands of patients suffering in pain and discomfort. Ask most people what the reason is, and they’ll give you a short answer: COVID. But this isn’t accurate.

Omicron has seen record case numbers and a sharp increase in hospitalisations, but the number of COVID patients in hospital has levelled off at only a bit over half what was seen during the alpha wave last winter. Plus, a substantial share of hospitalisations (up to 50% in some areas) have been “incidental” COVID cases – people in hospital for other reasons who have tested positive.

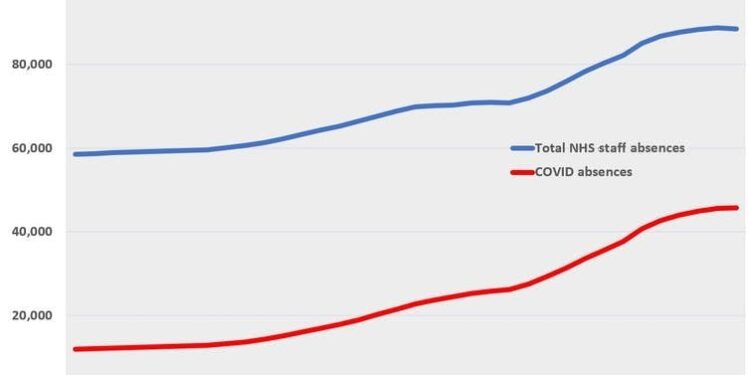

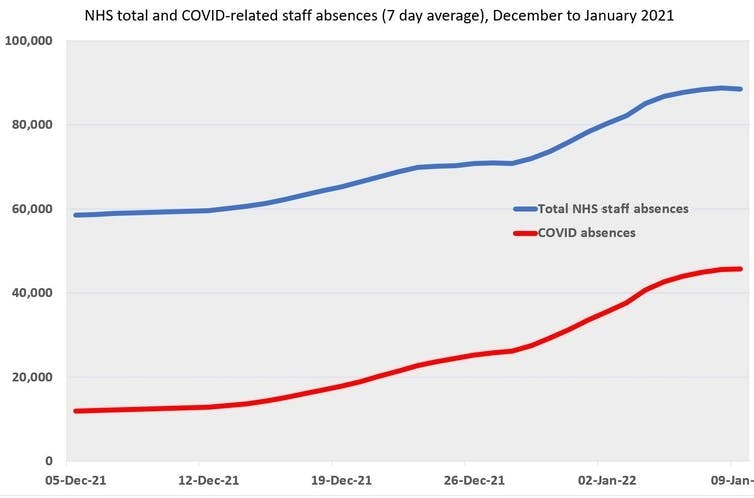

The new variant has had an even smaller impact on the number of COVID patients in intensive care, which has been relatively consistent since the middle of last summer. Arguably, the indirect effects of the omicron wave have had a larger impact on the NHS than the direct ones. COVID being so prevalent in the UK has meant that high numbers of COVID-positive healthcare workers have had to isolate at a time when the NHS has been under pressure.

NHS England

Truly, with the direct effects of omicron less severe than feared and cases now subsiding, COVID is not the biggest challenge facing the NHS. The concern over omicron these past few months has glossed over the more important long-term factors – such as the NHS’s stagnant workforce and demand for healthcare outstripping resources – that explain why this winter has been so bad.

Visible cracks

Elements of this crisis will be familiar to those following patterns of NHS pressure before the pandemic. While the problems are perhaps most visible at the beginning of the healthcare pathway (in the ambulance system and A&E departments) their causes are more at its end. We know that bed blocking, where patients are ready to be discharged but can’t be, often due to lack of adequate social care provision, has been a growing problem over the past decade.

It keeps hospital beds full, preventing new patients from being admitted, leading to backed-up patients in hospital A&E departments and in ambulances. Unfortunately, data on bed blocking has been lacking recently, as routine collection of data was “paused” by the NHS due to the pandemic. However a Freedom of Information request suggests it is worse than ever.

In conjunction with this, the health workforce has been increasingly under strain over the past decade, with the number of patients treated per year growing much faster than staff numbers. More and more, workforce pressures have been dealt with using short-term and temporary measures, including an rapid increase in nursing assistants to offset a more slow-growing nursing workforce, and an increase in temporary (or “locum”) doctors with a fall in permanent staff.

This underlying crisis has been exacerbated by the stresses of the pandemic, including treating patients with COVID, implementing restrictive measures to control the virus’s spread, which limit how hospital beds can be used, and, as previously noted, dealing with increased staff absences.

There are signs of improved numbers of students training as nurses and doctors since the onset of the pandemic. However, it will take time for the long-term workforce problems to be solved by increases in training.

The vaccine question

The latest fuel to be thrown onto this fire is the imminent sacking of unvaccinated NHS staff in patient-facing roles, which both doctors and nursing associations are now opposing. NHS management itself is said to now oppose this measure, given the relatively low effectiveness of vaccines against infection (although they are still very effective against severe disease).

While the push to mandate vaccines for healthcare workers is well meaning, it seems clear to most expert observers that sacking a substantial percentage (around 5% overall, higher in some areas) of NHS staff in the middle of a workforce crisis will harm rather than improve patient safety. A compromise perhaps would be to phase in mandatory vaccination for new NHS staff, without insisting current staff must be immediately vaccinated.

Social care is plagued by arguably worse staff shortages than the NHS, with an estimated 8.2% of roles unfilled in mid-2021 – higher than before the pandemic. Although the government announced a new funding package for health and social care with much fanfare in October 2021, most of these spending rises are still going to the NHS, with social care still being under-funded relative to demand. This means continuing low pay for care workers – and staff shortages as a result.

Throughout the pandemic, a great deal of public and political attention has been directed towards NHS performance, patient numbers in hospitals, and the skills and dedication of NHS staff. As we gradually emerge from the acute phase of the pandemic, there is scope to harness this attention to try and solve the longer-term issues in our NHS.

However, that will require a move away from crude statistics on COVID patient numbers and the belief that the coronavirus is the root cause of the NHS struggling this winter. If we’re to avoid the similar crises happening again, there needs to be a more nuanced and practical focus on improving the NHS’s funding, its workforce and the pathways into and out of the hospital system, from primary care to social care.

![]()

Peter Sivey receives funding from the National Institute for Health Research.