Nostalgia has somewhat of a bad reputation – particularly for its recent influence on politics and society. The emotion is supposed to persuade, delude and charm people into making electoral decisions.

For example, Brexit has been blamed by some on Britain’s “nostalgia for the past”, while Donald Trump’s “Make America Great Again” slogan is perhaps the best encapsulation of nostalgia’s political power.

But, while the politics of nostalgia seem to be particularly potent today, the emotion has a long, troubled history.

As I have explored in my new book Nostalgia: A History of a Dangerous Emotion, there are few feelings as ubiquitous, yet tricky to pin down, as nostalgia. One of the reasons for this is perhaps because nostalgia, more so than other emotions, has undergone a particularly radical transformation over the past three centuries. Just a hundred years ago or so, it was not merely an emotion – but a sickness.

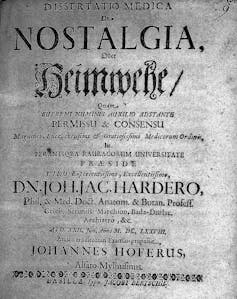

Nostalgia was first coined as a term – and used as a diagnosis – by the Swiss physician Johannes Hofer in 1688. Derived from the Greek nostos (homecoming) and algos (pain), this mysterious disease was a kind of pathological homesickness. In patients, it caused psychological disturbances such as lethargy, depression and confusion.

But it also had physical symptoms such as heart palpitations, open sores and disturbed sleep. It was thought to be a serious, intractable disease – difficult to treat, almost impossible to cure. For unlucky victims it could prove fatal, with sufferers slowly starving themselves to death.

Since it was first identified in Switzerland, it was thought to be a peculiarly Swiss condition. The country was so beautiful, its air so refined, that anyone who left was at risk of dire physical consequences. Students, mercenaries and domestic servants were supposedly particularly vulnerable – young people who had been compelled to leave home and might then find it difficult to return. Nostalgia plagued the Alps but soon spread through Europe – an emotional pandemic, with prominent peaks in autumn when the falling leaves prompted melancholics to think of the passage of time and their own mortality.

Dissertatio medica de nostalgia, oder Heimwehe / [Johann Hofer]. Wellcome Collection.

In 1781, an Ipswich doctor called Robert Hamilton was working in a barracks in the north of England when he encountered a concerning case of nostalgia. A soldier who had recently joined the regiment was sent to see Hamilton by his captain. He had only been a soldier for a few months, was young, handsome and “well-made for the service”. But “a melancholy hung over his countenance, and wanness preyed on his cheeks.”

The soldier complained of “a universal weakness” – a noise in his ears and a giddiness of his head. He slept poorly and was off his food and drink. He sighed deeply and frequently – something, it seemed, weighed heavy on his mind. All treatments proved ineffective and he was admitted to hospital. He remained bedbound for nearly three months, and became gradually more emaciated. He was struck down with a fever and spent the nights bathed in sweat. Hamilton expected the worst and considered him a lost cause.

One morning, a nurse mentioned to Hamilton that the soldier spoke obsessively of home and his friends. The young man had kept up a running commentary on his desire to return home ever since arriving at the hospital. When Hamilton went up to see the stricken man, he asked him about his native Wales.

The soldier responded with real enthusiasm, became obsessive and would not stop talking about the glories of the Welsh valleys. He asked Hamilton if he would let him go home. The doctor promised that as soon as the soldier’s physical condition had improved, he could return for a six-week break. The patient revived at the very thought. The young soldier, now much recovered, set off to Wales with a spring in his step.

Nostalgia then travelled from Europe via the ships carrying enslaved Africans to North America. At this point, it had not yet acquired the positive association with trivial self-indulgence that it has now. Instead, it had the power to kill and disable, and was taken very seriously. In fact, it was one of the leading causes of non-combat death during the American Civil War. The last recorded victim of nostalgia was a foot solider fighting on the western front in 1917.

In the 20th century, nostalgia changed. It parted ways with homesickness and transformed – first into a psychological disorder, then into the emotion we know today.

However, early psychoanalysts took a dim view of nostalgia and people prone to its indulgence. They thought they were neurotic, retrograde, overly-sentimental and unable to face reality. Writing in the shadow of the second world war, they were suspicious of patriotism: “Why does an old country, often of wretched and beggarly existence, become a fairy land to victims of nostalgia?” But these psychoanalysts were also snobbish, believing nostalgia was more common among the “lower classes” than the cosmopolitan elite.

Juli Hansen/ Shutterstock

These views, while no longer held by therapists or psychologists, are still prevalent in political discussions about nostalgia. Indeed, nostalgia’s reputation today, particularly as an influence on politics, culture and society, is not so honeyed.

In 2016, for example, nostalgia was invoked as an explanation for two major electoral events: the presidential success of Donald Trump and the Brexit vote. But when journalists and critics used nostalgia to explain these cataclysmic geopolitical moments, they all too often deployed it as a kind of diagnosis – something to explain away seemingly wayward or irrational political decisions. As the historian Robert Saunders put it, in reference to Brexit, the debate marked out the Leave vote as “a psychological disorder: a pathology to be diagnosed, rather than argument with which to engage”.

Nostalgia might not be a disease anymore, but it hasn’t shed all of its old associations. It remains, for many, an explanation for what they view as the less progressive, more irrational political choices some people make.

While no longer deadly, it remains a dangerous emotion.

![]()

Agnes Arnold-Forster does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.