When states give driver’s licenses to undocumented immigrants, it affects nondrivers, too — even the littlest ones. Babies born to immigrants from Mexico and Central America are bigger and healthier in states that make that change, our research shows. The longer a law is in effect before a baby is conceived, the stronger the effect.

We are a sociologist and an epidemiologist who examined the birth records of more than 4 million babies born to Mexican and Central American immigrants who lived in states that adopted expanded driver’s license policies between 2008 and 2021.

We found that incidences of low birth weight – infants weighing less than 5 pounds, 8 ounces at birth – fell 7% in those states, and the average weight of newborns rose by 5.2 grams.

To validate our results, we replicated the analysis for U.S.-born, non-Hispanic white pregnant people living in the same states. We didn’t expect to see any effect from the law for this group — and indeed, we found none.

Why it matters

This research shows how state policies tied to immigration can affect immigrant families’ health and well-being, even when those policies have nothing to do with health.

Over the past two decades, state governments have passed increasing numbers of immigration laws. While some of these policies aim to drive out immigrants, others seek to give them more protections. Such laws can apply to immigrants of many legal statuses, including undocumented and legal permanent residents. And they can affect U.S. citizens, too.

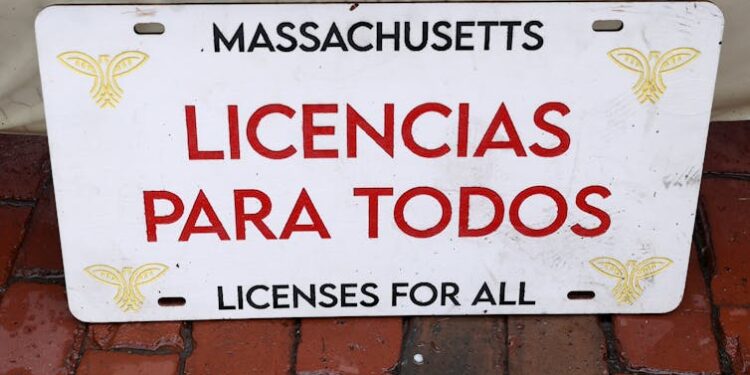

Nineteen states have passed laws letting undocumented people get driver’s licenses, most recently Minnesota in 2023. Lawmakers in several other states, including Indiana and Michigan, have introduced similar measures. Florida, on the other hand, has not only made it illegal for undocumented immigrants to get licenses, but it also won’t recognize licenses issued to undocumented immigrants from other states.

David L. Ryan/The Boston Globe via Getty Images

Previous research has shown how restrictive policies can negatively affect the health of immigrants and their children. Our study is one of the first to examine how supportive state-level immigration policies, like those expanding access to driver’s licenses, impact health.

Higher birth weight is linked to better health throughout life, including improved cognitive development in infancy and reduced risk of cardiovascular and metabolic disease in midlife. It’s also associated with increased earnings across adulthood.

Since birth weight is an important indicator of future health and economic outcomes, the benefits of letting undocumented people get driver’s licenses could be felt for decades to come.

The laws we analyzed were implemented between 2013 and 2020, a period marked by increasing hostility toward immigration. Amid promises of mass deportation under a second Donald Trump administration, these results are a timely reminder of the critical role of state policymaking on immigrant families’ health.

What still isn’t known

We don’t know exactly why expanding access to driver’s licenses would lead to healthier birth outcomes for immigrants.

One possible explanation is that these laws reduce stress. Exposure to stress, both before and during pregnancy, increases risk of negative birth outcomes. And for many undocumented immigrants and their loved ones, driving without authorization — a criminal offense that can jeopardize one’s immigration status or even lead to deportation — is a profound stressor.

What’s more, obtaining a driver’s license can make it easier for undocumented immigrants to work, to find health care and to access other resources — all of which can contribute to higher birth weights.

It will take more work to tease out the influence of all these factors. For this reason, we think researchers should investigate the potential health effects of other inclusive state immigration policies, such as eligibility for in-state college tuition for undocumented residents, labor protections for noncitizens, and the provision of state health insurance regardless of legal status.

As our research shows, the well-being of immigrant families depends on more than just what’s happening in Washington.

The Research Brief is a short take about interesting academic work.

![]()

Margot Moinester received funding from the National Science Foundation (Award No. SES-1655497). The views presented here are solely her own.

Kaitlyn Stanhope receives funding from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Health Resources and Services Administration, and Georgia Department of Public Health. The views presented here represent solely her own views.