People living with Alzheimer’s disease and other related disorders may experience stigma related to their diagnosis or to aging. Along with their caregivers, family or friends who accompany them through life, they risk being shamed, misunderstood and negatively labelled. Research shows that early-stage diagnosis impacts the quality of life of individuals.

We are researchers affiliated with a community project named What connects us — Ce qui nous lie, based in Montréal.

This project is dedicated to the complex task of finding ways to improve the quality of life of people living with Alzheimer’s and other related disorders, and their caregivers. In addition to our backgrounds in communication, medical anthropology, rehabilitation and social network analysis, we are part of an interdisciplinary team that brings expertise in sustainable design (Anabel Sinn), community development (Chesley Walsh) and public health (Seiyan Yang).

The goal of the project is to create an enriched web of resources in the community by linking the artistic, mental health and academic sectors — and to help decrease stigma at the intersection of Alzheimer’s and other related disorders, mental illness and aging.

We have learned that part of our work needs to be about investigating how to communicate about dementia. Vocabulary surrounding neurocognitive disorders must be carefully chosen. Our aim here is to present our experiences surrounding the use of Alzheimer’s terminology in this public health community investment project.

Table of Contents

Speaking about ‘dementia’

Throughout history, there has not been a consistent way to talk about Alzheimer’s disease and other related disorders.

Fortunately, we have come a long way since, in the West during the 18th century, people living with neurocognitive disorders were described as “imbeciles” and “senile people.”

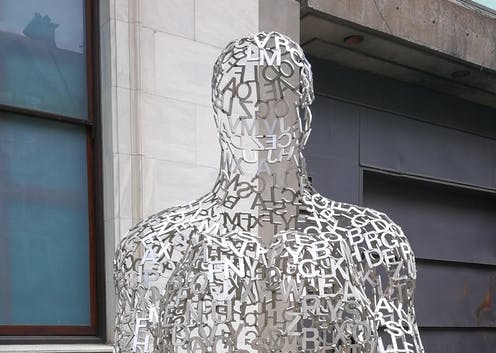

A vast array of more neutral terms than “dementia”, such as “neurocognitive disorders” are used today.

(BruceEmmerling/Pixabay)

Activities for people with Alzheimer’s

We are working with community-based organizations, health institutions and the public sector, mainly based in Montréal, to facilitate a handful of different activities such as art therapy, laughter yoga, dance therapy, reminiscence activities and short public screenings for people living with Alzheimer’s and their carers.

Through our partnership with this diverse group of collaborators, one of the hidden challenges of our work was around the wording and vocabulary to describe and inform our potential participants (persons living with Alzheimer’s and related disorders and their carers).

Whether we are working with community-based organizations and health institutions, we observe that there isn’t an agreed-upon approach to talking about neurocognitive disorders. This impacts our daily work and actions.

Different terminology, no agreement

We are constantly adjusting to the vocabulary chosen by our partners, which requires sensitivity to the implications of different terms depending on the primary language of choice (French or English) or the sector (health or community-based). The Public Health Agency of Canada, for example, prefers to use the word “dementia.” Some organizations consider “dementia” a stigmatizing word and do not use it at all, while others prefer it and ask us to use it.

In some cases, our partners prefer the wording “Alzheimer’s disease and related disorders.” Other partners choose the phrase “neurocognitive illness.”

The lack of common terminology can cause multiple back-and-forth discussions when promotional tools for artistic activities need to be sent. One simple poster can be edited numerous times because the wording is considered stigmatizing or to have a negative connotation. We had to change the vocabulary of our project website more than once, shifting from “people living with dementia” to “people living with neurocognitive disorders” to “people living with Alzheimer’s and/or other related disorders.”

Even more challenging is the task of translating vocabulary between French and English in the province of Québec. The Public Health Agency of Canada uses the word “démence” to name its dementia-related program in French, a term now perceived as stigmatizing by many francophones.

Collaborative tools needed

Our aim is to build bridges between public health, community organizations, mental health and academic sectors. That task also falls to other organizations and research projects that are spreading public awareness in the community for language that can be shared to build bridges between different sectoral cultures as well as linguistic ones.

We need more initiatives in the community through language to make sure that we create a space where people from different communities facing “dementia” feel connected and accepted.

(Shutterstock)

Community-based projects need more shared language for resource maps and lists, making it easier to identify organizations working to support people living with Alzheimer’s and other related disorders and sensitive to the nuances and potential marginalization that words can cause.

Public health institutions in Canada continue to increase the focus on “dementia” as the number of seniors in the population continues to grow. According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, the senior population “is expected to rise 68 per cent over the next 20 years.” As a result of that increase, “the prevalence of dementia more than doubles every five years for Canadians age 65 and older, from less than one per cent for those age 65 to 69 to about 25 per cent for those 85 and older.”

Building common language

Our experience points to a call for greater discussion about the words we choose and what they mean. This discussion matters as it can create some common ground in order to build long-term relationships between all organizations helping the community of people living with Alzheimer’s and other related disorders.

We cannot ignore the fact that people develop neurocognitive disorders, whatever vocabulary we choose. We also cannot deny that with a growing population of aging people, building long-term and sustainable approaches to supporting our community members living with Alzheimer’s and their carers is a matter of urgent concern.

![]()

Arnaud Francioni works for the What Connects us – Ce qui nous lie project, which is funded by a grant from the Public Health Agency of Canada.

Ce qui nous lie~What connects us receives funding from the Public Health Agency of Canada and in-kind contributions from engaged partners.

Patricia Belchior and Thomas Valente do not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and have disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.