In the spring of 2024, residents of the south Devon harbour town of Brixham kept falling ill. Their symptoms – including “awful stomach complaints, bad diarrhoea and severe headaches” – went on for weeks. A retired GP who ventured to the pub after finally recovering from the illness recalled that, when someone asked those present to “raise their hand if they hadn’t had the bug”, not a single hand went up.

Given the controversies about raw sewage discharges that were swirling at the time, the drinking water seemed an obvious suspect. Many local residents contacted their water provider, but by late April, South West Water was still insisting the water was safe to drink, and that all tests for contaminating bacteria had returned negative.

Then suddenly, the company issued an urgent “boil it” note to thousands of households in Brixham and nearby villages and towns in the Torbay region. A tiny parasite that causes the intestinal disease cryptosporidiosis had been discovered in the water supply.

The contamination was eventually pinpointed to a defective valve under a stretch of farmland which had allowed cow faeces to enter three holding tanks of drinking water – downstream from the main water works, and also from where the water’s quality was routinely tested.

According to South West Water, the outbreak ultimately affected 17,000 households. While the official record shows 77 confirmed cases of “crypto”, as it is commonly known, the UK Health Security Agency only began surveying residents in the second week of July – long after the outbreak began.

The contamination of an entire region’s water supply, with thousands of households forced to rely on bottled water or boiling their tap water for months, is shocking. But as experts in the history of waterborne disease outbreaks and public health, what concerns us most is how quickly the story has moved on – as if nothing could be done and it was “just another infection”.

Given the UK was once known for its revolutionary sanitation projects, we want to understand what systemic issues – from inadequate infrastructure to corporate cover-ups to lax legislation – lie at the heart of this inability to keep the water clean and people free from waterborne infection. Or put another way: why can’t Britain get its shit together?

The residents of Torbay have a particular right to ask this question. In the summer of 1995, the same Devon holiday region (known as the “English riviera”) experienced the UK’s first major outbreak of waterborne disease – also cryptosporidiosis – since the water industry was privatised by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government in 1989. More than 250,000 residents were sent a “boil it” notice. By the end of the summer, there had officially been 575 cases and 25 hospitalisations.

A year later, the environment secretary John Gummer took South West Water to court under section 70 of the 1991 Water Industry Act. This was the first time a British water company had been taken to court for providing water unfit for human consumption – but the case was thrown out after evidence provided by the Drinking Water Inspectorate was ruled inadmissible.

The ruling fuelled public fears that water companies, like other newly privatised state enterprises, could not be held properly accountable for their mismanagement. These concerns have grown over the subsequent three decades, as South West Water – and England and Wales’s other nine private water and sewage companies – have regularly been accused of prioritising healthy shareholder dividends over the public’s health.

This article is part of Conversation Insights.

Our co-editors commission long-form journalism, working with academics from many different backgrounds who are engaged in projects aimed at tackling societal and scientific challenges.

Many of the world’s modern systems of public health surveillance have their origins in innovations Britain introduced in the mid-19th century, including continuous water supply, sewage filtration and routine governmental investigation of disease outbreaks.

And yet Britain has never managed to eradicate systemic failures when it comes to providing safe, clean and accessible drinking water to its citizens. To understand why not, we need to start by revisiting Britain’s major cholera and typhoid outbreaks of the 19th- and early 20th-century, which at their peaks killed hundreds of people every day.

Table of Contents

‘The power of life and death’

The colossal power of life and death wielded by a water company supplying half a million customers is something for which, till recently, there has been no precedent in the history of the world. Such a power ought most sedulously to be guarded against abuse.

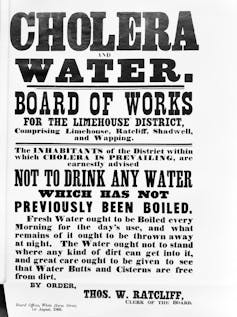

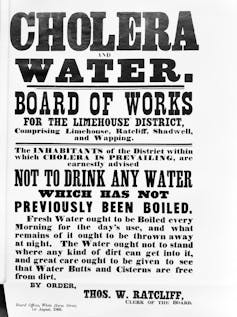

These prophetic words were written by the British government’s first ever chief medical officer, John Simon, in 1867. He was responding to one of the country’s worst water-related scandals: the 1866 cholera epidemic that killed 5,596 people in the East End of London.

Wellcome Collection, CC BY-NC-ND

A legal mechanism should have prevented this appalling loss of life. According to the 1852 Metropolis Water Act – introduced in response to previous cholera epidemics in the 1830s and 40s that had also killed thousands – London’s eight private water companies had been compelled to move their river water intakes away from the polluted city centre (where the river was still tidal), and to perform water filtration before it reached consumers. Yet the act was powerless to prevent the return of cholera in June 1866, this time because of the failings – and denials – of the East London Water Company.

Within weeks, the epidemic was killing hundreds of Londoners every day. Holborn’s medical officer of health, Septimus Gibbon, reported the deaths of two children on the same day at the home of a cigar maker in Cannon Street, observing:

The house where these children resided is in clean and fair sanitary condition, but there is an old and partly disused sewer running close at the back of it, in the rear of Great James Street, which the sanitary authority is unable to destroy, because three houses in Green Street claim a right to drain into it.

At the height of this cholera outbreak, the East London Water Company denied all accusations from government epidemiologists that it was responsible for the deaths. In August 1866, the company’s chief engineer, Charles Greaves, wrote a letter to The Times declaring that, for several years, “not a drop of unfiltered water has been supplied by the company for any purpose”. But his statement was quickly contradicted by two local residents, who told the East-End News they had discovered eels in their water pipes.

In the end, pioneering epidemiologists discovered that the East London Water Company – wrestling with both a blocked water filter and unusually high demand in early June 1866 – had opened the sluice at its uncovered Old Ford reservoir, drawing in unfiltered water and unleashing diarrhoeal horrors on the residents of east London.

Yet despite being in clear violation of the 1852 act, the company argued other factors were to blame for the cholera outbreak – even including the suspect morals of East End residents. In his evidence to a parliamentary select committee, engineer Nathaniel Beardmore pointed to the dangers of an overcrowded East End “populated by dock labourers, sailors, mechanics in the new factories, and great numbers of laundresses”.

Ultimately, while the East London Water Company received lots of bad press, it was given no official sanctions. A pattern of denial and obfuscation had been established that water companies have regularly employed ever since, when accused of being responsible for life-threatening water infections.

‘Dead bodies are being washed ashore’

In the wake of the 1866 cholera outbreak, Simon, the pioneering chief medical officer, argued that the way to eradicate deadly health outbreaks was a combination of more surveillance of water companies and more preventive public health measures based on epidemiological investigations. This would mean carefully monitoring sickness data from around the country, and sending in epidemiological experts at the first sign of crisis – not waiting until after an outbreak had exploded.

But despite Simon’s urgings, it would take another shocking water-related scandal for the British government to get serious about the dangers of untreated sewage.

Wikimedia Commons

One late-summer evening in September 1878, the Princess Alice, a paddle steamer with more than 800 people on board, smashed into the coal ship Bywell Castle in the middle of the River Thames. The Alice was virtually sliced in two, and sank within minutes in sight of North Woolwich pier.

Two hours earlier, 75,000 gallons of raw sewage from the outflows of Joseph Bazalgette’s much-heralded underground sewerage system – constructed to rid London of its “great stink” and only just completed – had been discharged into the same stretch of river, forming a noxious cloud of air and hideously contaminated water. A survivor of the disaster would later recall:

Both the taste and smell were something dreadful … Having been down to the bottom and having rose again with my mouth full of it, I could give a very good picture of it – it was the most horrid water I ever tasted and the smell was also equally bad.

This was Britain’s worst inland waterway tragedy, claiming around 650 lives. A report in The Times described dead bodies “continually being washed ashore along the whole course of the river from Limehouse to Erith … It will be some days before this rendering up of the dead will be at an end.”

While the victims died by drowning or asphyxiation due to being trapped inside the sinking boat, the descriptions of the state of the river water and air caused outrage among the public. In response, the government rushed in a new law that all sewage must be treated before being discharged into rivers. Extensive new treatment facilities were commissioned, beginning in east London, and a Royal Commission on Sewage Disposal was established in 1898 – the first to set official standards for the treatment of wastewater.

But while these efforts meant the threat of cholera was largely eradicated from British drinking water, its deadly waterborne cousin, typhoid fever, continued to wreak havoc. So prolific were these outbreaks – including the worst episode of typhoid in modern British history, when nearly 2,000 people were infected and more than 140 died in Maidstone, Kent, in 1897 – that by the turn of the century, more than 150 British towns and cities had taken responsibility for providing and regulating water into their own hands.

Maidstone Museum/Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-NC-ND

This new vision of municipal responsibility was encapsulated by the pioneering mayor of Birmingham, Joseph Chamberlain, who spearheaded a massive public ownership programme for provision of gas, schools, libraries and city parks. In 1876, he established the Birmingham Corporation Water Department after buying the private Birmingham Waterworks Company for £1,350,000 (over £195 million at today’s prices).

Progressives argued that removing private industry from the provision of water and other key services would ensure the standards of health and hygiene that modern towns and cities required – and that this was more important than company profits. Or as Chamberlain put it:

We have not the slightest intention of making profit … We shall get our profit indirectly in the comfort of the town and in the health of its inhabitants.

The march of municipalisation

Maidstone’s deadly typhoid outbreak would see the town go down in history as the world’s first municipality to attempt widespread water sterilisation, when its reservoir and mains water supply were disinfected with a solution of chloride of lime in 1897 (it proved “a difficult procedure that required several attempts”). In time, this initiative would lead to global water chlorination programmes that are estimated to have saved millions of lives by preventing the spread of dangerous bacteria including Salmonella Typhi, the cause of typhoid fever.

Shortly afterwards, in 1902, London joined the march of municipalisation, when the Metropolitan Water Act created the largest public water system in Britain with the purchase of the city’s private companies. The East London Water Company alone was purchased for nearly £4 million – over £600 million today.

The rationale was threefold: cost savings from delivery at scale, an ethos of civic responsibility, and the belief that publicly owned water could be more closely monitored, preventing waterborne outbreaks in the future.

By the mid-20th century, a public-private hybrid was the norm for water provision in Britain – and the scale of the resulting public investments in waterworks was staggering. However, the argument that these would lead to long-term savings was disputed – with a 1920 parliamentary committee on the impact of the Metropolitan Water Act concluding:

Not only has there never been any savings in total cost, [but] the actual expenditures of the [new London-wide water] board have been in excess of the total of the eight undertakings whose properties were taken over. The cost of the water supplies … has risen.

Municipal water projects may not have saved money, but did they save lives? A 2016 study found that municipalisation of Britain’s water supply from the late-19th century resulted in a reduction of typhoid fever by 19%. The city of Oxford experienced an initial decline in typhoid mortality from the 1880s due to improved sand filtration and municipal piped water, followed by a sharp decline when chlorination of the water was introduced in 1930.

And yet, in the second half of the 20th century, sewage treatment across Britain consistently failed to meet the standards demanded by laws imposed decades earlier, according to a report by the government regulator Ofwat:

The desire to dispose of sewage as cheaply as possible led to a lack of investment in sewage treatment by many councils, and the number of river pollution incidents increased through the 1960s. This, in turn, increased the treatment requirement of river water abstractions. By the end of the 1960s, 60% of all sewage treatment works were estimated to be failing to meet the standards established at the end of the 19th century.

Thatcher’s radical strategy

By the early 1970s, England and Wales still possessed a motley crew of public and private systems for dealing with sewage and water. In all, there were 160 different water companies (some public, some private), 130 sewerage authorities, and 29 river authorities. Where operational risks were usually shouldered by the private sector, the public sector typically carried all the (enormous) financial risks associated with the building of water treatment infrastructure.

In 1973, Edward Heath’s Conservative government sought to end this confusing array of localised water and sewerage provision. Its latest version of the Water Act established ten new regional water authorities – based not on the political might of cities but the dominant regional river systems in England and Wales. It was an ambitious but largely sensible attempt to secure the long-term health of Britain’s water supply. In early February 1973, Geoffrey Rippon, secretary of state for the environment, told his House of Commons colleagues:

This is a radical reconstruction. I suggest it is none the worse for that. It takes its place alongside the reorganisation of local government and of the health services in this government’s overhaul of the administration of the country, to keep pace with the problems with which we shall have to deal through the remaining decades of this century and into the next.

Rippon was seeking approval for a programme of carefully coordinated public and private investment – but his plea fell on deaf ears among Conservative MPs and their colleagues across the aisle. Instead, a more radical strategy was introduced by Heath’s successor as Tory leader, Margaret Thatcher.

Rather than investing any more public money in Britain’s water infrastructure, Thatcher sought to put Britain’s entire system of water provision back in the hands of the private sector. A decade after she came to power in 1979, and despite a public outcry and many referendums, she finally achieved this through the Water Act of 1989. This turned the regional water authorities in England and Wales into limited companies, and offered lucrative regional monopolies to the highest bidders. (In Scotland, the plans to privatise were met with particularly strong opposition, and its public schemes remain to this day.)

In one infamous speech in the House of Commons, Thatcher’s argument rested on a simplistic economic case for long-needed investment: “It will be the people who want those improvements in water who will have to pay.”

This was a reversion back to the Victorian origins of Britain’s approach to water provision. But the prime minister had orchestrated her case well. Restrictions imposed by her government on public borrowing since the early 1980s had made it impossible for the regional water authorities to borrow money for investments for over a decade.

At the same time, the 1980s saw a steadily growing concern for the environment among the British public and rising demand for improvement of its waterways. The UK’s embarrassing failure to meet European obligations which it had co-designed made privatisation seem like a sensible last resort, even though such a policy had no precedence in any other developed country.

Yet it remained one of the most unpopular policy decisions of the Thatcher government. In 1994, the Daily Mail – usually an ardent supporter of the Conservative party – condemned it under the headline “The Great Water Robbery”, declaring:

When it was privatised in 1989, the water industry was hailed as the jewel in the crown of the Thatcherite privatisation programme … In reality, the water industry has become the biggest rip-off in Britain. Water bills, both to households and industry, have soared. And the directors and shareholders of Britain’s top-ten water companies have been able to use their position as monopoly suppliers to pull off the greatest act of licensed robbery in our history.

Globally, the full-scale water privatisation of England and Wales remains an exception, other than for a few World Bank-led initiatives in developing economies. Most European countries have opted for a coexistence of private and public bodies.

In England and Wales, selling off water providers as regional monopolies led to unsustainable price hikes, with company after company prioritising shareholders over customers from the get-go. Whereas publicised investment strategies implied that sewerage systems had, on average, a reliable lifetime of 280 years, in reality many are crumbling away – with even conservative evaluations limiting their lifetime to about 110 years, such that some urgent upgrades are now urgently needed.

‘Poisoned consumers’

In the summer of 1995, when Torbay experienced the UK’s first major outbreak of a waterborne parasite since Thatcher’s privatisation programme, investigations by Public Health England traced the outbreak to the Littlehempston water treatment facility near Totnes – but there was no conclusive evidence on how the cryptosporidium parasite had entered the water.

South West Water offered £15 to each affected household, but claims of reputational and economic damage from the outbreak were growing by the hour. Legal action against the company followed but the case was thrown out. After installing a new filtration system, South West Water stated it had “absolutely minimised” any future risk of a stomach bug emerging from the faulty facility. Yet as litigation had been unsuccessful, there was no pathway to test this pledge and hold the company to account for any future failures.

The familiar cop-out of downplaying the seriousness of any faults – whether in monitoring and regulating water quality, or a lack of investment in infrastructure – was voiced again in March 1997 by Conservative MP James Clappison, who noted during a debate on cryptosporidium that “most incidents are relatively minor happenings”.

Earlier that same month, Thames Valley Water had issued another dreaded “boil it” notice, this time to 300,000 customers in Hertfordshire and North London. Emboldened by the failed legal case in south Devon, the company robustly refused compensation claims and offered a single paltry payout of £10 to affected customers.

In Scotland, meanwhile, water had been retained in public ownership. Writing in The Scotsman in March 1997, columnist Lesley Riddoch remarked that in England and Wales, there was obviously “still no legal requirement for companies to compensate poisoned consumers”.

Following Tony Blair’s landslide victory in May 1997, the new Labour government promised tighter oversight of the water industry – including an increased threat of prosecution for companies that transgressed. But for Adrian Sanders, then Torbay’s LibDem MP, this didn’t go far enough, as he told the local Herald Express newspaper in May 1998:

I am concerned there still isn’t anything to allow independent watchdogs access into water treatments for tests. There isn’t a clearcut way for residents to seek compensation if they are the victims of the bug.

In the 12 months following Blair’s election, all ten of England and Wales’s water and sewerage companies were found guilty of environmental offences. Thames Water and Anglian Water were prosecuted eight times in 1999, and by 2001, Severn Trent led the “serial offenders” table with 494 pollution incidents since the new government came to power. But the associated fines were usually negligible. Wessex Water, a subsidiary of US energy company Enron, was fined only £5,000 (plus costs) for discharging 1 million gallons of raw sewage into Weymouth marina in Dorset one August bank holiday.

More recently, government-induced fines have increased. Since 2015, the UK Environment Agency has prosecuted 59 water and sewerage companies for over £150 million. Yet outbreaks of waterborne illnesses from dodgy, stinking, and contaminated water sources remain all-too-common. In May 2024, Conservative MP Anthony Mangnall condemned South West Water’s response to the outbreak of cryptosporidium in his south Devon constituency:

I think this is contemptible and just generally incompetent – it’s put a lot of people’s health at risk. That, to me, is one of the most serious indictments because they were made aware of this by a large number of people, including myself … So to not actually respond in a manner that would safeguard public health, I think, is deeply problematic.

Is Britain’s water system broken?

In the era of COVID-19, we mostly hear about epidemiology as the science of predictive modelling. But at its core, epidemiology is a detective science of outbreak investigation. This means carrying out proper diagnoses to verify the pattern of an outbreak, clarify the presence of a common infective agent, elucidate conditions that might accelerate the epidemic, then form a hypothesis about its cause.

Yet outbreak investigations seem too often to be a thing of the past. “The nearest I heard of any surveys,” one Brixham resident noted earlier this year, “was post-Pilates coffee conversations: have you had the bug?”

As the earlier, failed legal challenge against South West Water in 1996 recalls, to develop a successful prosecution, a case needs good detective work involving up-to-date water monitoring as well as epidemiologists on the ground, counting cases.

In Keir Starmer’s first prime minister’s questions on July 24, the very first question posed – by Calum Miller, LibDem MP for Bicester and Woodstock – challenged the new prime minister to accept that “Britain’s water system is broken”.

The new government – in echoes of the Blair ministry almost 30 years earlier – had already promised in the king’s speech to strengthen the powers of the water regulator Ofwat, increase compensation levels for “boil it” notices, and make it easier for customers to hold water company bosses to account in special hearings. These measures point in the right direction, but they won’t go far enough to restore trust in British water after so many decades of failure.

Almost 150 years on from the original “march of munipalisation” led by Birmingham’s Mayor Chamberlain and other towns and cities, the corporate status of British water providers is back under scrutiny. While the new Labour government officially has no plans to re-nationalise Britain’s water, we’re squarely back in conversations about whether Britain’s best bet with water safety is a more draconian regulation of privatised companies, or a return to nationalisation.

With Thames Water in distress and steep price hikes ahead, this is a difficult political and economic gamble for the government and the water regulator. But even if the government ends up having to take some companies into “special measures”, this won’t address the overpowering issue of a leaking, ailing and stinking water and sewerage infrastructure that is unfit for purpose.

If the future of water companies continues to be private, public or somewhere in between (which seems most likely), a key question is how to maintain public and political will for infrastructure investments on the massive scale that is required – amid the “black hole” in public finances identified by the chancellor Rachel Reeves.

But ensuring safe and clean water also requires faster epidemiological investigation and new monitoring systems. When things go wrong (and the next crypto outbreak will not be far away), affected customers require a proper outbreak investigation – not tokenistic compensation and lukewarm promises from their water provider.

Epidemiological analysis should commence as soon as a failure is noticed – not like at Brixham earlier this year, where a proper survey only began nine weeks after the “boil it” notices were sent out. Investigations carried out too late risk becoming complicit in any attempt to cover up the scale of a water crisis.

A better future depends on proper outbreak investigation in concert with appropriate legislation, which offers the chance to provide true accountability. If evidence collected in timely fashion by an independent agency stands up in court, legal routes to compensation become a viable option for customers. This in turn should provide a considerable motivation for water providers – private or otherwise – to finally start cleaning up their shit.

For you: more from our Insights series:

-

The discovery of insulin: a story of monstrous egos and toxic rivalries

-

A century ago, the women of Wales made an audacious appeal for world peace – this is their story

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

![]()

![]()

Lukas Engelmann receives funding from the European Research Council, project # 947872 and from the British Academy.

Jacob Steere-Williams does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.