Every day we are exposed to things like pollution and ultraviolet light which increase our risk of illness. Many people take on additional risks — due to tobacco smoke, fast food or alcohol, for example.

But there is a less-recogized exposure that is even more common than smoking and increases the risk of heart disease, diabetes, cancer, chronic lung diseases, sexually transmitted infections, chronic pain, mental illness and reduces one’s life by as much as 20 years.

This public health hazard that hides in plain sight is childhood adversity: experiences like physical abuse, sexual abuse and neglect.

Table of Contents

Childhood adversity is common

In Canada, one child in three is physically or sexually abused or witnesses violence between adults in their home. Other adversities such as emotional neglect, living in an unsafe neighbourhood or experiencing prejudice and bullying are even more common. Studies in the United States show about 60 per cent of children and teenagers have these adverse childhood experiences, or ACEs. The more severe the exposure, the greater the health risk.

The reason that ACEs contribute to so many diseases is that they are associated with many things that trigger other causes of disease. Think of ACEs as a “cause of causes.”

Health risk behaviours and physiological changes

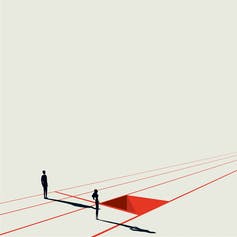

(Shutterstock)

As kids who have had adverse experiences grow up, they are more likely to smoke, to drink excessively and to use nonprescription drugs. They are more likely to engage in risky sexual activities and to become obese. Not all kids with ACEs take on risky activities, of course, but enough to contribute to ACEs’ health consequences.

Growing up in conditions that are consistently frightening or stressful affects the biology of developing bodies, especially the development of the systems that regulate our reactions to threats, from predators to viruses. ACEs are even associated with changes in our chromosomes that are linked to early mortality.

Interpersonal and psychological effects

As psychiatrists for adults who experience physical and mental illness in combination, our patients often tell us about the personal impact of ACEs. One man said he did not “have even the slightest shadow of a doubt that a loss of human connection is the most substantial negative impact” of these experiences. The health costs of human disconnection are profound. Indeed, lacking interpersonal support may hasten mortality as much or more than smoking, excessive drinking, inactivity, obesity or untreated high blood pressure.

The psychological effects of ACEs may be more obvious and can include fearful expectations, a conviction that one is unworthy of love or protection, unregulated anger or shame and discombobulating memories of bad events.

(Shutterstock)

It greatly increases the risk of depression, anxiety disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder and addictions. The one in three adults who experienced childhood sexual or physical abuse or witnessed interpersonal violence at home have at least twice the incidence of these disorders compared to others.

And then the dominoes fall: mental illness greatly increases the likelihood, burden and consequences of physical illness. To give just one example, in the months after experiencing a heart attack, those who are depressed are several times more likely to die.

So, we see that ACEs don’t only lead to one kind of trouble, but to many.

Social determinants of health

Finally, the burden of illness is not distributed fairly. Maintaining health is more challenging for those who are disadvantaged by poverty, lack of education, language barriers, discrimination and living with the continuing systemic harms of colonization and multi-generational trauma.

(Shutterstock)

Childhood trauma has a complex relationship with these social determinants of health. On one hand, ACEs are not unique to marginalized groups and can occur across all strata of society. On the other hand, the risk of experiencing ACEs may be greater in some groups and the consequences of ACEs may multiply as social forces interact.

For example, childhood trauma is strongly associated with behaviours that increase the risk of sexually transmitted infections. About half of the people living with HIV have experienced childhood abuse. HIV is also more common in groups that face discrimination, including men who have sex with men, people who use injectable drugs, Indigenous people and immigrants from countries in which HIV is endemic.

Intersecting components of personal experience and identity attract stigma and discrimination, which in turn influences mental health, self-care and one’s ability to navigate a healthcare system that has multiple barriers and gaps. It is a complex web and ACEs contribute to this complexity.

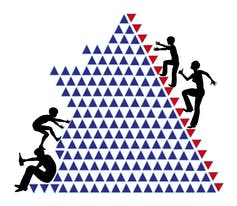

A cause of causes

Events that occur in childhood may contribute to cascading health risks over one’s lifetime. There are so many paths to illness interacting with one another over decades and compromising health in so many ways, that it should be no surprise that childhood adversity is a profound public health problem.

It is time that we, as a society, recognized ACEs as the malignant force that they are. Those affected need to be treated with compassion and also with awareness of the long-lasting effects of early adversity on health. Research that helps us understand the lifelong impact of ACEs could help guide prevention of chronic illnesses and mental health issues in the many people who experience adversity during childhood.

![]()

Robert Maunder receives funding from Sinai Health and the University of Toronto as Chair of Health and Behaviour at Sinai Health and receives royalties from the University of Toronto Press for Damaged: Childhood Adversity, Adult Illness, and the Need for a Health Care Revolution.

Jon Hunter receives funding from Sinai Health and is The Pencer Family Chair in Applied General Psychiatry at Sinai Health. He receives royalties from the University of Toronto Press for Damaged: Childhood Adversity, Adult Illness, and the Need for a Health Care Revolution.