Africa Studio/Shutterstock

How do scientists read a person’s DNA? – James, aged 11, Thame, UK

DNA (which stands for deoxyribonucleic acid) contains all the information needed to make your body work. It is also surprisingly simple.

DNA is made from four chemical building blocks, which are arranged one after each other. This sequence is the instruction manual for your body. The building blocks are called adenine, thymine, guanine and cytosine, but we usually just call them A, T, G and C.

Curious Kids is a series by The Conversation that gives children the chance to have their questions about the world answered by experts. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to curiouskids@theconversation.com and make sure you include the asker’s first name, age and town or city. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we’ll do our very best.

The information in your DNA is bunched into sections called genes. The genes are like sentences in an instruction manual.

Most genes control the everyday running of your body – how it grows hair, digests food or carries oxygen around. So 99.9% of your DNA is exactly the same as everyone else on the planet. The rest is what makes you unique. For example, if you have blue eyes, then a few of the letters in some genes will be different from someone with brown eyes.

As we grow, cells in our body divide. One cell becomes two. Every time this happens each of the new cells needs a full copy of DNA. DNA makes this easy, because it’s made of two strands. When a cell divides the strands split up, and a new copy is made of each one. Let’s look at how this is done.

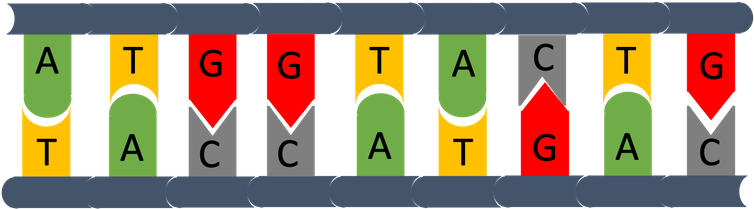

The letter A on one strand is always opposite the letter T on the other, and G is always opposite C. So a short double strand of DNA might looks like this:

Mark Lorch, Author provided

Let’s see what happens with one of the strands in a dividing cell. First a T is added opposite the first A to make:

Mark Lorch, Author provided

Then an A gets attached to the T like this:

Mark Lorch, Author provided

Next, C get placed opposite G:

Mark Lorch, Author provided

And so on until a whole new double-stranded piece of DNA is made.

Reading DNA

We can use this knowledge of how DNA copies itself to read a person’s DNA.

To do this, a scientist puts the DNA into four tubes. Then they add all the machinery that the cell uses to copy DNA, and lots of extra As, Ts, Cs and Gs into each of the tubes.

Next, they add some DNA letters that have been changed so they can’t join with the next letter in the sequence. You can think of them like pieces of Lego, but with flat tops so you can’t add a brick on top of it. Let’s call these special DNA letters A*, T*, G* and C*.

Each of our four tubes gets some of the special DNA letters added to it: A*s in the first tube, T*s in the second, G*s in the third and C*s in the fourth.

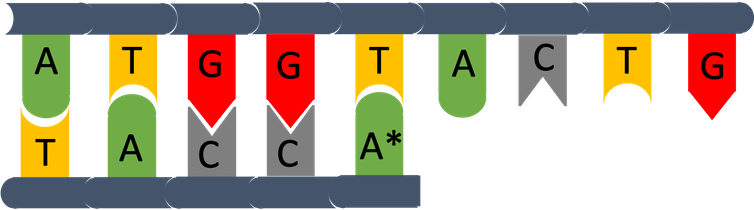

Let’s imagine what happens with our DNA sequence in the tube containing A*.

First, just like before, T is added opposite the first A to make:

Mark Lorch, Author provided

Next, though, an A* might get added to make this:

Mark Lorch, Author provided

If this happens, then the next letter can’t get attached to the A*. This is as long as this stretch of DNA gets.

But there’s plenty more DNA and letters in the tube and in some cases a normal A will have been added at that point, followed by two Cs to make this:

Mark Lorch, Author provided

Next there is a choice again. If an A* gets added the DNA sequence will look like this:

Mark Lorch, Author provided

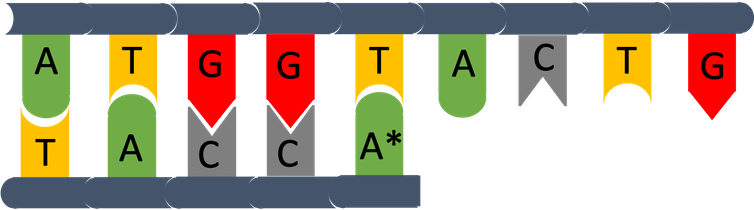

Every time we reach the point where we need to add an A there is a chance an A* might get added, which stops the DNA getting any longer. So in the end these DNA strands get made:

Mark Lorch, Author provided

The scientist reading the DNA knows that each strand in this tube ends in an A*. She then counts how many pairs are in each strand of DNA. By doing this, she can work out that the 2nd, 5th and 7th letters are all As.

She then does exactly the same thing with the other tubes and works out that the 1st and 6th letters are Ts, the 3rd, 4th and 9th letters are Cs and the 7th is a G. By putting that all together, she can read the whole DNA sequence.

Reading DNA is useful because sometimes the letters in the genes aren’t quite right, like a misspelled word in a set of instructions. This might cause some of your cells to not work properly.

For example, just one wrong letter in one particular gene might mean someone is more likely to become diabetic, or get cancer when they are older. Reading someone’s DNA allows doctors to spot and treat these diseases before they become too bad.

![]()

![]()

Mark Lorch does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.