The World Health Organization estimates that dogs bite tens of millions of people per year, mainly children. Canada, meanwhile, has not published a report on dog-bite injuries in children and youth since 2003.

That 2003 report contained alarming information. Among infants and toddlers, for example, more than two-thirds required emergency treatment because dogs had bitten their faces, heads or necks. And more children between the ages of five and nine received emergency treatment for dog-bite injuries than for ice-hockey injuries. As for youth aged 10 through 14, dog-bite injuries accounted for more emergency department visits than trampolining.

Beyond health care, policies do exist to prevent dog-bite injuries and lessen their impact. The Calgary model hinges on dog licensing. Calgarians currently pay $42 to license a sterilized (spayed or neutered) dog, and $67 per unaltered dog. As of January 2022, these fees will increase by $1.

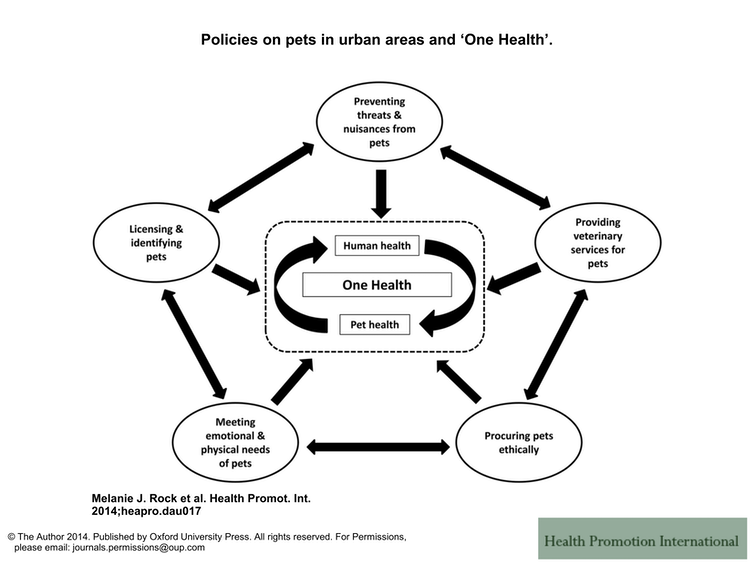

(Melanie Rock), Author provided

Licensing augments traceability following dog-bite injuries, or after aggressive behaviour that stops short of dog-bite injuries (for example, chasing people in parks). People who purchase licences for their dogs contribute to society in other ways too. Due to its licensing program, Calgary has the highest return-to-owner rate and the lowest pet euthanization rate in North America, according to the city’s department of animal services.

(Morgan Mouton)

Our team’s previous research underscored that the potential for reunifications and for saving the lives of dogs impounded by the city has contributed to buy-in with dog-licensing compliance in Calgary. After all, few people anticipate that their pet dogs will attack other dogs or bite other people — not least children.

The Calgary model has influenced policy debates and decisions elsewhere. Examples include Edmonton, Montréal and as far away as Australia. At least fourin five dogs have licences in Calgary, compared with about two-thirds of Edmonton’s dogs, and fewer than a third in Toronto.

Such stark differences translate into dog-bite prevention that is more effective and efficient in Calgary than in Edmonton, for instance. The more owners license their dogs, the quicker-biting dogs and their owners can be located — first in a database and then within a city. And the more people who license their dogs, the more money that a municipality can invest in human-animal services.

Stella the Rottweiler

The case of Stella the Rottweiler illustrates the Calgary model for dog-bite prevention. Two dogs were fighting in a Calgary park, when one of the dogs bit the other dog’s companion. A bystander telephoned the city to report the incident. The bystander identified the biting dog as a Rottweiler called Stella. Within minutes, by consulting the city’s database for licensed dogs and their legal owners, a peace officer on patrol nearby could list addresses and owners for 17 Rottweilers named Stella.

After spotting a handful of potential matches, the officer reached the owner and issued fines for the dog-bite injury plus the dog fight, all the while recommending ways to stop dog-bite injuries from happening. Calgary’s database for licensed dogs allowed Stella the Rottweiler to be traced and this dog’s legal owner to be confronted and fined, all in a day’s work.

Not all biting dogs and their owners can be traced so readily, not even in Calgary. For example, on June 6, 2021, at 6:42 p.m., Calgary Police Services turned to Twitter to warn residents about a dog and to seek assistance with finding this animal. The dog, described as a white pit bull, had “bitten two people and should be considered dangerous.”

Later that evening, at 9:39 p.m., CTV amplified this bulletin. At 10:20 p.m., Calgary Police Services sent out an update via Twitter: the injured child had been “transported to hospital to be treated for non-life-threatening injuries,” but the dog still had “not been captured.”

When policy-makers (or journalists) call for more ambitious dog-bite policies, they tend to highlight bans and restrictions based on dog breeds. This policy approach is often called breed-specific legislation. This emphasis on dog breed is unsurprising, considering that media coverage of dog-bite injuries tends to fixate on dogs described as pit bulls.

(City of Calgary), Author provided

Even so, terriers such as pit bulls were no more likely to bite people and cause serious injury than other types of dogs, including miniature or “toy” dogs, according to Calgary’s own dog-bite data. Internationally, breed bans have not consistently decreased dog-bite frequency or severity. By emphasizing dog licensing, dog welfare and a collaborative approach to public safety and enforcement, the Calgary model has achieved recognition as a viable alternative.

Calgary’s experience in dog-bite prevention teaches us that while public discussion and media debates often focus on dog breed or type, policy implementation remains critical. For this reason, changes approved in June 2021 to Calgary’s Responsible Pet Ownership Bylaw may not be opportune. These changes emphasize stricter enforcement, without much consideration for licensing and traceability of dogs.

Policy priorities

In our view, government policies should address two key issues that remain neglected in dog-bite prevention. First, more should be done to improve co-ordination across sectors. During Calgary’s pet policy review, for instance, Alberta’s health-care records on dog-bite injuries did not receive consideration, neither did medical charts for children bitten by dogs.

The second issue is social justice. Traceability is a key element for dog-bite prevention, and despite success stories such as “Stella the Rottweiler,” traceability is still sorely lacking. The unsuccessful search on June 6, 2021, for a “white pit bull” serves as but one tragic example. Even so, traceability following aggressive incidents involving dogs — up to and including dog-bite injuries — is far better in Calgary than in other cities across Canada and internationally.

Calgary considered licensing subsidies for low-income households with dogs while reviewing its Responsible Pet Ownership Bylaw, but has yet to pursue that policy option. That’s a shame, because in lower-income neighbourhoods, dog licensing might fall below Calgary’s enviable average. If so, then the children and families at highest risk for dog-bite injury and life-long trauma have the least protection. We suspect that traceability remains lowest in lower-income neighbourhoods under the Calgary model, but we cannot say for sure. That’s not due to a lack of data.

Unfortunately, Calgary’s pet policy review did not extend to the geographic and socio-economic distribution of dog-bite injuries and investigations, which could have informed the policy recommendations put before council in June 2021.

Fortunately, it’s not too late to look for geographic and socio-economic patterns in the dog-bite data held by Alberta Health Services, the City of Calgary and the Public Health Agency of Canada. And it’s not too late to hear directly from dog-bite victims and their families, people whose dogs have attacked or bitten others, citizens who report dog-bite injuries as well as concerns about dogs’ own welfare, and health-care professionals such as paramedics, pharmacists, physicians, psychologists, social workers and veterinarians.

Research like this can and should inform policy implementation, starting with Calgary. That would make the Calgary model for dog-bite policy and prevention worth emulating for years to come.

![]()

Funders for the research underpinning this article include the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (CIHR).

For this work, Morgan Mouton has been funded by the O'Brien Institute for Public Health and Cumming School of Medicine (University of Calgary). Previous funding sources include the French Ministry for Higher Education and Research, as well as the French National Research Agency.