For nearly 200 years, Florence Nightingale’s name has been synonymous with gentle compassion and mercy.

In the mid-19th century, Nightingale became perhaps the most celebrated woman of her era – second only to Queen Victoria – for instituting sanitation practices that sharply cut death rates among British soldiers fighting in the Crimean War. A handsome bronze statue in London’s Waterloo Place has immortalized Nightingale as a slight, graceful figure carrying a lamp, the embodiment of selfless womanhood.

But this iconic image overshadows many other accomplishments. Nightingale also transformed nursing into a respectable profession, founded the world’s first nursing school, used the relatively new science of statistics to improve health care outcomes and redesigned hospitals. She was also one of Western history’s first advocates of health care for all.

Over the five years I spent researching and writing my biographical novel about Nightingale, “Flight of the Wild Swan,” published March 12, 2024, my vaguely sentimental notions about her were replaced by respect for her visionary achievements. I resolved to bring into sharper focus this woman who, along with her legendary work as a war nurse, spent half a century pioneering advances in health care.

The 19th century ushered in a series of revolutionary medical advancements. Nightingale’s contributions were a significant part of this era.

Tony Baggett/iStock via Getty Images

Table of Contents

Called to serve the suffering

Florence Nightingale was born in Florence, Italy, on May 12, 1820, to William and Frances Nightingale, a wealthy British couple. The Nightingales raised their two daughters, Florence and her sister Parthenope, on two estates in England. William homeschooled the girls, giving them the equivalent of his own Cambridge University education.

From an early age, Nightingale displayed a formidable intellect, with a particular interest in mathematics. At 16, she experienced a transcendent call to serve the suffering, a call that eventually coalesced into her determination to become a nurse. Her family objected, however, because nursing was an unsuitable occupation for young Victorian women of privilege. It was considered disreputable work with a status even lower than that of servants.

But Nightingale gradually overcame her family’s objections, receiving training in Germany and France. In 1853, she became the superintendent of a small hospital in London for “distressed gentlewomen.” The majority of her patients were educated, unmarried governesses whose health had broken down under the strain of long hours of work and negligible pay.

A little over a year later, she was on her way to the Crimean War.

National Library of Medicine

Bringing sanitation to medicine

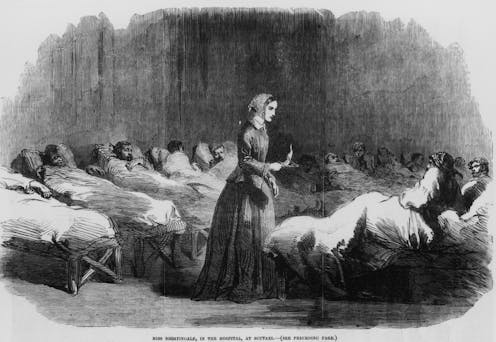

In October 1854, Nightingale brought 38 female nurses under her supervision to Scutari Barrack in Constantinople – today’s Istanbul. Originally a gargantuan stone barracks for the Turkish army, Scutari was now a British hospital housing thousands of wounded English and Irish soldiers.

At Scutari, she and her nurses found few provisions, little medicine or edible food, and overcrowded hospital wards full of rats, lice and raw sewage. More soldiers were dying of cholera and other infectious diseases than of battle wounds. Nightingale and her nurses set to work cleaning and procuring food, soap, bandages, medicine, clean bedding and clothes for patients. As living standards improved, Scutari’s appalling death rate began to decline.

It was there that Nightingale’s reputation as the “Angel of the Crimea” and the “Lady with the Lamp” began. Wartime journalists telegraphed their newspapers with dramatic accounts of her work. These stories ignited the public’s imagination and created the indelible image of a slight, feminine figure carrying her lamp through hospital wards at night.

In January 1855, British Prime Minister Henry John Temple, 3rd Viscount Palmerston, dispatched a newly formed Sanitary Commission to the Crimea to investigate high mortality rates in the military hospital. Nightingale observed firsthand the dramatic decline in death rates as the commission cleaned out the hospital’s befouled sewer systems, limewashed its walls – in effect killing surface bacteria – and made numerous other sanitation improvements.

Nightingale was already a proponent of hygiene, fresh air and proper diet in medical care; this experience made her a committed sanitarian.

When the war ended in 1856, Nightingale returned home, permanently bedridden with chronic brucellosis, then called “Crimean fever.” This didn’t stop her from spending the rest of her life applying herself to improving health care systems in Great Britain and other countries.

Using numbers to cure

Statistics was a relatively new science in Nightingale’s time, but it aligned with her early interest in mathematics. Ultimately, Nightingale would come to believe that statistics used to help reduce mortality rates were “the true measure of God’s purpose.”

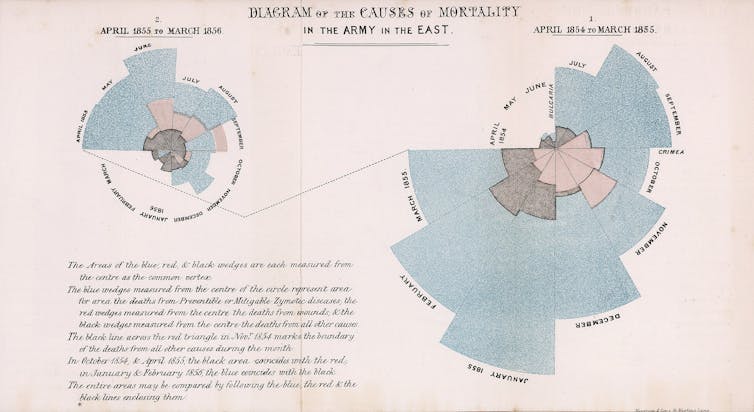

Collaborating with William Farr, a leading figure in applying statistics to epidemiology, Nightingale analyzed extensive data on army mortality rates during the Crimean War, proving that most deaths were attributable to preventable diseases rather than battlefield injuries. She was particularly innovative in her use of graphic diagrams such as her famous “rose,” or “coxcomb,” diagram, rightly believing that attractive visuals were more impactful than the dry numbers tables favored by the era’s statisticians.

Wikimedia Commons/Public Domain

As a result, in 1858, in recognition of her use of the statistical method in army sanitary reform, Nightingale was inducted into the Royal Statistical Society as the organizations’s first female fellow. In 2020, the Royal Statistical Society established an annual Florence Nightingale Award for Excellence in Health and Care Analytics.

In a revolutionary step, Nightingale extended her statistical methods and data visualization to other areas, ranging from hospital administration and health care management to public sanitary reform and the sources of preventable diseases. These analyses further exposed the causes of both military and civilian mortality.

Educating future nurses

In 1860, seeking to elevate nursing into both a science and an art, Nightingale founded the world’s first school of nursing: the Nightingale Training School for Nurses at St. Thomas’ Hospital, London.

The female students – numbering 20 to 30 at a time – lived at school and wore nurses’ uniforms to rigorous classes on anatomy, surgical nursing, physiology, chemistry, sanitation and ethics. By the 1880s, Nightingale had accepted the newer “germ theory” of disease spread, and this became part of the curriculum.

At the conclusion of the one-year program, Nightingale sent her nurses into the world as certified and paid health professionals.

By the turn of the century, the school had graduated nearly 2,000 certified nurses. Known as “Nightingales,” they fanned out across Great Britain to practice skilled patient care, develop nursing care systems, teach, train and mentor.

The Nightingale Training School became a pioneering model for nursing education throughout Great Britain. Similar schools would be established in Africa, America, Australia, Canada and other countries.

Nightingale also wrote a bestselling book, 1859’s “Notes on Nursing,” that guided Victorian wives in keeping members of their households healthy.

Advocating for public health

Nightingale’s long, ultimately successful effort to bring trained nurses and midwives into England’s and Ireland’s notorious workhouses has gone largely unacknowledged.

During Victorian times, paupers in workhouses who became ill could be cared for only by other destitute workhouse residents. Nightingale wrote numerous articles emphasizing the need for public health nurses to care of the sick in these institutions, and during the 1860s she called for the abolition of England’s harsh poor laws.

As a result of these efforts, workhouse nursing reforms gradually spread across England.

I believe that a more fully realized understanding of Nightingale’s life and achievements beyond being “the lady with the lamp” can provide an inspirational role model for those considering careers in nursing, medical science and public health today.

![]()

Melissa Pritchard does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organization that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.