Three people in the UK have tested positive for Lassa fever – including a newborn infant, who has unfortunately died as a result. Hundreds of close-contact healthcare workers are now in isolation as a precaution. This is the first time since 2009 that cases of the virus have been reported in the UK.

The patients are said to have contracted the virus in west Africa, where there has been a wave of infections reported in Nigeria. Many people are understandably concerned about this virus, especially given no vaccines exist against it and there are limited antiviral medicines to treat the infection it causes. But in the UK, given the small number of people that have been affected, the threat to the wider community is low.

Despite the recent news coverage, we’ve actually known about Lassa fever for over 50 years – though it’s likely been around much longer. The Lassa fever virus (which causes Lassa fever disease) was first discovered in 1969 during an outbreak in Nigeria. It was named after the town Lassa in the north east near Cameroon, where the outbreak first began.

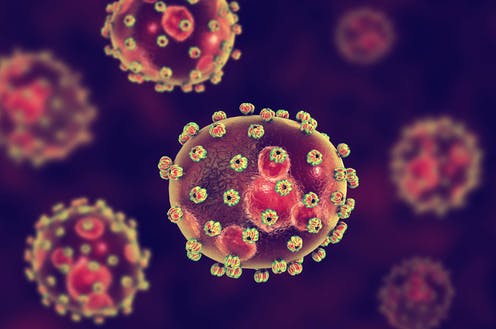

Lassa fever is what is called a “viral haemorrhagic fever”, similar to Ebola. But while it can cause problems with how you control the movement of fluids through your body (meaning fluid may sometimes leak out of the blood vessels), this rarely happens. Thankfully, around 80% of people don’t get very sick when they contract Lassa fever, and usually only experience flu-like symptoms, such as a headache, sore throat and fever.

But in around 20% of patients, severe illness can happen. This can affect the body’s organs, including the liver, brain, gut and lungs. If you manage to survive this severe form of the disease, it’s highly likely you may experience long term disability – such as hearing loss.

For around 1%-3% of cases, Lassa fever is fatal. Unfortunately, we don’t yet understand why some people get severe disease and no clear risk factors are established.

Rat-borne virus

Lassa fever causes an estimated 5,000 deaths a year, and up to 300,000 infections throughout west Africa, where the disease in endemic.

Lassa fever is a zoonotic virus, meaning it comes from animals. It’s naturally found in a type of common wild mouse-like mammal called a multimammate rat that can live in close contact with humans. While the virus doesn’t usually cause illness in these rats, it can be excreted in their urine and saliva.

Marek Velechovsky/ Shutterstock

After coming in contact with affected urine or saliva, a person can be exposed to the virus if they touch their eyes, mouth or any scratches they may have. You can also inhale it through contaminated dust particles. Infection is most common during the west African dry season, between December and April.

Given its relatively long incubation period of one to two weeks, Lassa can easily hitch a ride in people across the world from its home in west Africa. But once a person has been exposed, they typically don’t pass it along to other people.

However, it has sometimes been known to spread when people are in close contract, especially if they’re exposed to contaminated fluids. While such contact between carers and contaminated fluid from patients is uncommon, great care is still taken in treating patients sick with the disease. You’re most likely to spread Lassa if you become severely ill from it.

Given how dangerous Lassa fever disease is, work with the virus must be carried out at the highest level of biological safety. Only a handful of labs are capable of working with Lassa fever virus, which may be why so few antiviral drugs have been developed. No vaccine has currently been developed for Lassa Virus, and so health authorities have named it a priority disease for researchers developing ways to combat infection.

Lassa virus already causes considerable burden across Africa. We should expect to see more cases of Lassa outside the area as international travel takes off after the pandemic. However, with the right precautions, it’s unlikely major outbreaks will take place outside of endemic areas. This is because people outside of these regions have little contact with the infected animals.

The UK patients who contracted the virus will be cared for until they recover. Close contacts will continue to be closely monitored and tested for infection. If further positives are detected, they too will be isolated and contacts quarantined – similar to what occurs with COVID. But it’s unlikely that there’s much of a cause for concern for the wider public, except for those who may travel to the affected countries.

![]()

Connor Bamford receives funding from Wellcome-Trust, UKRI and BMA Foundation.