The good news about monkeypox is that it doesn’t spread that well between humans. Because of this, the current monkeypox outbreak will probably be kept under control by isolating infected people and their contacts, coupled with selected vaccination.

Fortunately, monkeypox is similar enough to smallpox that the smallpox vaccine is effective against both viruses. Rather than vaccinate everyone, we will most likely use “ring vaccination”: vaccinating contacts of known infected people to keep the outbreak under control.

Ring vaccination works when there are limited cases that can be easily identified. This approach was used in the past for outbreaks of Ebola (highly effective Ebola vaccines were developed after the 2014 epidemic to little fanfare) as well as to eradicate smallpox in the 1970s.

Unless there is surprising new information about this strain of monkeypox, selective isolation and ring vaccination will be enough – this is not another COVID-19. But the smallpox vaccine, vaccinia, which has saved millions of lives already, is one of the strangest things that humanity has ever created. This is a virus that we domesticated for our own uses as a vaccine, repurposed for other vaccines and may have been accidentally released into the wild.

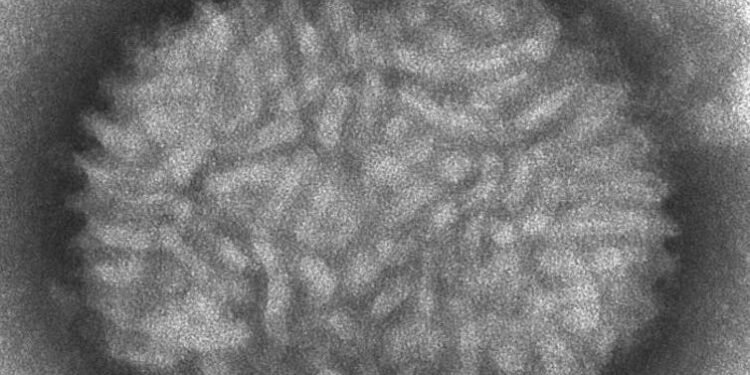

CDC/Cynthia Goldsmith

Table of Contents

Vaccinia – when humans domesticated a virus

Many people know the story of Edward Jenner, the English doctor who, in the late 18th century, noticed that milkmaids who had caught cowpox were protected from smallpox. So he started vaccinating: intentionally giving people cowpox to protect them from smallpox.

After a while, it became easier to harvest smallpox vaccine from the vaccinated, rather than from cows. Once a human was spiked with the cowpox virus, they developed pustules a few days later, and then virus was taken by puncturing the pustule and passed it on to the next person.

This dirty technique obviously carried across all sorts of skin infections but also gave cowpox time to adapt and mutate to its new ecological niche, eventually becoming the vaccinia virus we know today. This means that vaccinia is a virus that has been cultivated by humans for our own benefit. So vaccinia is what I would call a “domesticated virus”.

Vaccinia, however, is genetically distinct from cowpox. This is because it was cultured for a long time in human-to-human transmission chains.

As the smallpox vaccine is made with the live vaccinia, it can spread from recently vaccinated people to unvaccinated contacts.

Vaccinia can be used to vaccinate against other viruses

The AstraZeneca vaccine against COVID was a viral vector vaccine, where a strain of adenovirus had the spike protein from the novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) added in.

Vaccinia was one of the first viruses to get this treatment almost 40 years ago. In the 1980s, we knew we had a safe and effective vaccine for smallpox, which was going out of use once smallpox was eradicated. If we used DNA splicing (a brand new concept at the time) to put in genes from other viruses, we could make vaccines against them as well.

A lot of vaccines have been through clinical trials which use modified versions of vaccinia. Outside of a pandemic this is generally a slow process from testing to approval, but one vaccinia-based vaccine has been approved: Mvabea, which is an approved vaccine for Ebola.

Accidentally released into the wild?

Bovine vaccinia is a disease endemic to Brazilian milking cattle. It causes rashes and lesions on the udders that can spread to the hands of workers who milk the cattle.

This is an economic problem in Brazil as infected cattle can’t be milked (and sometimes need to be put down) and workers have to take time off sick. Bovine vaccinia is a reminder that viruses regularly spread from livestock to humans, and we need to handle live animals in a hygienic way. It also reminds us that viruses can travel the other way.

The Bovine vaccinia genome has a remarkable resemblance to vaccinia. This isn’t too surprising as vaccinia originated from European cowpox, and bovine vaccinia might be a new world variant of cowpox. However, bovine vaccinia might also be due to early vaccination efforts in South America.

Several groups believe that bovine vaccinia is most likely to be an older smallpox vaccine that “escaped” from a vaccinated farm worker into the local population of cows and has adapted to its new environment.

Much like a domesticated pet cat that wreaks havoc in the local bird population, it looks as if our domesticated virus is wreaking havoc on Brazilian milk farming.

![]()

Ben Krishna does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.