“I hope we have persuaded [the minister] of the need to do more, not merely to reduce industrial noise but to help people who have suffered industrial deafness. I confess to having some direct and personal interest in the subject … I am one of those who has to pin his ear to the amplifier as I am partially deaf … I attribute this not to advancing years, but to my former industrial experience in the engineering industry.”

Harold Walker was a man obsessed with making work safer. As this extract from a 1983 House of Commons debate on industrial noise shows, the longtime Labour MP for Doncaster did not stop campaigning even after his greatest professional achievement, the Health and Safety at Work Act, passed into UK law 50 years ago.

Walker was a “no nonsense” politician who brought his own experiences as a toolmaker and shop steward to inform legislation that is estimated to have saved at least 14,000 lives since its introduction in 1974.

But despite this, the act has for nearly as long been a source of comedic frustration at perceived bureaucratic overreach and unnecessary red tape. The phrase “health and safety gone mad” was common parlance in the late 20th century, and in 2008, Conservative leader David Cameron told his party conference: “This whole health and safety, Human Rights Act culture has infected every part of our life … Teachers can’t put a plaster on a child’s grazed knee without calling a first aid officer.”

Read more:

The UK’s Health and Safety at Work Act is 50. Here’s how it’s changed our lives

Such criticisms feel like a precursor to today’s torrent of complaints aimed at “woke culture”. But as a senior occupational health researcher and member of the University of Glasgow’s Healthy Working Lives Group, I want to stand up for this landmark piece of legislation, which underpins much of our work on extending and improving working lives – ranging from the needs of ageing workers and preventing early retirement due to ill health, to the effects of Long COVID on worker efficiency and mental health and suicide prevention at work.

Sometimes, our group’s research highlights changes to the act that are needed to fit today’s (and tomorrow’s) ways of working. But its fundamental principles of employer responsibility for safety in the workplace have stood the test of time – and feel more relevant than ever amid the increase of insecure work created by today’s zero hours “gig economy”.

But my reasons for writing about the act are personal as well as professional, because Harold Walker – who in 1997 became Baron Walker of Doncaster – was my grandfather. As a boy, he would tell me terrifying stories about his time working in a factory. I did not realise that one of them would prove to be a seminal moment in the formulation of Britain’s modern health and safety legislation.

Table of Contents

‘It happened both quick and slow’

The details always remained the same, however many times he told me the story. His friend and workmate had been trying to fix a pressing machine in the toolmaking factory where they both worked. My grandfather vividly painted a scene of extreme noise, sweating bodies, rumbling machines and dirty faces.

The machine lacked guards and suddenly, as his friend worked, his sleeve got caught in the cogs. “It happened both quick and slow,” my grandfather recalled. He described the man being pulled into the machine, screaming, while he and other colleagues tried, unsuccessfully, to wrench him free. Too late, the machine was shut down. By this point, the cogs were red with blood, the man’s arm crushed beyond repair.

Despite its obvious culpability, my grandfather said their employer offered his friend no support, made no reforms, and simply moved on as if nothing had happened. My grandfather was deeply affected by the incident, and I believe it played a key role in shaping the rest of his political career.

Walker would serve as a Labour MP for 33 years, holding roles including minister of state for employment (1974-79) and deputy speaker of the House of Commons (1983-92). His fierce support for Doncaster and the city’s main industry, mining, earned him a reputation as a key figure in industrial relations – and saw him struggle to maintain neutrality during the 1984 miners’ strike.

As deputy speaker, no one appears to have been safe from his charismatic if somewhat tyrannical rule – he once reportedly chided the prime minister, Margaret Thatcher, for straying off-topic. Fellow Labour MP Barbara Castle described him as “a short, stocky man who looked like a boxer and behaved like one at the despatch box – very effectively”.

The act he championed was born from anger and his unshakable belief that workers’ lives were worth protecting. As a result of his impoverished upbringing – born in Audenshaw near Manchester, his father had variously been a hat-maker, rat-catcher and dustman – my grandfather was obsessed with making sure I had properly fitting shoes, since ill-fitting hand-me-downs as a child had left his feet permanently damaged. This belief in small but essential acts of care underpinned his approach to both life and politics.

How the act was created

For decades after the second world war, as Britain sought to rebuild its shattered economy and infrastructure, some of its workplaces remained death traps. In 1969, 649 workers were killed and around 322,000 suffered severe injuries. This reflected, at best, a lack of knowledge about the need for enhanced worker safety – and at worst, a blatant disregard for workers’ health on the part of businesses and the UK government.

For centuries, coal mining had been one of Britain’s most hazardous industries. Miners faced the constant threat of mine collapses, gas explosions and flooding, and disasters such as at Aberfan in 1966, where a coal spoil tip collapsed onto a school killing 116 children, became tragic markers of the industry’s dangers. Older miners would often succumb to diseases such as pneumoconiosis (black lung), caused by inhaling coal dust day after day.

Likewise, unprotected shipbuilders and dockers, construction workers, steelworkers and railway employees all faced a threat to life merely for doing their job, including falls from unsafe scaffolding, molten metal accidents and train collisions.

In the textile mills of Manchester and beyond, workers toiled in poorly ventilated factories, inhaling cotton dust that led to byssinosis, or “Monday fever”. Poisoning and exposure to dangerous chemicals plagued workers in tanneries and chemical plants.

While the 1952 London smog had brought nationwide attention to large-scale respiratory diseases when some 4,000 excess deaths were recorded over a fortnight (leading to the first effective Clean Air Act in 1956), respiratory ailments in the workplace were typically considered just another occupational hazard in any industry that involved dust or toxic fumes, from mining to shipbuilding to textiles. Meanwhile another lurking, silent killer – asbestos in buildings – would only be recognised in the late 20th century as the cause of deadly conditions such as mesothelioma.

Historian David Walker has argued that many British companies favoured reparations over prevention because it was more cost-effective, resulting in thousands of workers permanently being disabled and unable to work. Determined to change this systemic injustice, Walker first revealed his ambition to bring in new protections for workers in 1966, when he proposed “some necessary amendments to the Factories Acts”. But progress was slow and difficult.

Over the years, whenever my grandfather told me about those parliamentary debates and private arguments while digging his garden in Doncaster, I swear he would stick his fork into the earth more forcefully. His stories were full of names like Barbara Castle, Michael Foot, Philip Holland and Alfred Robens that meant little to me as a boy. But even to my young self, it was obvious the creation of the act required extraordinary levels of determination and resolve.

The Insights section is committed to high-quality longform journalism. Our editors work with academics from many different backgrounds who are tackling a wide range of societal and scientific challenges.

In 1972, the Robens Report – commissioned by Castle, then Labour’s secretary of state for employment and productivity – laid more concrete groundwork by calling for a single, streamlined framework for workplace safety. Working alongside legal experts, industry leaders and union representatives, my grandfather was a central part of the team attempting to translate these recommendations into practical law. A lifelong smoker, he painted vivid pictures to me of the endless debates in smoky committee rooms, poring over drafts late into the night.

This was a cross-party effort involving MPs and peers from all sides, united by a shared determination to tackle appalling workplace conditions, who faced significant opposition both within and outside the commons. Despite this, the act’s journey through parliament was anything but smooth – beset by disagreements over small details or questions of process, such as when a 1972 debate veered off course to discuss the nuances between “occupational health” and an “occupational health service”.

In May 1973, Liberal leader Jeremy Thorpe taunted his parliamentary colleagues about the lack of progress on the act, shouting across the floor at Dudley Smith, the Conservative under-secretary of state: “No one would wish the honourable gentleman to sit there pregnant with ideas, but constipated about giving us any indication of what was intended.”

One of the thorniest issues was whether the law should prescribe specific rules or take a broader, principle-based approach. The latter would ultimately win out, reflected in the now-famous phrase “so far as is reasonably practicable”, meaning employers must do what is feasible and sensible to ensure the health and safety of their workers. As the bill was read yet again in April 1974, Walker – by now the under-secretary of state for employment – was congratulated on his dogged determination by opposition Tory MP Holland:

“The honourable member for Doncaster has spent so much time and effort on this subject in previous debates that it is fitting he should now be in his present position to see this bill through its various stages … In this bill, we have such a broad approach to the subject, and I welcome it on those grounds. The fact the last two general elections interrupted the promotion of safety legislation causes me a little trepidation about the fate of this bill. But I hope this parliament will last long enough to see it reach the statute book.”

Health and safety ‘goes mad’

When it finally passed into law in July 1974, the Health and Safety at Work Act aimed to ensure every worker had the right to a safe environment. It introduced a fundamental shift in accountability, making employers responsible for their employees’ welfare through financial penalties and public discourse, and established an independent national regulator for workplace safety, the Health and Safety Executive.

Two years later, when asked in parliament if he was satisfied with how the act was operating, Walker replied: “I shall be satisfied with the operation of the act when I am sure that all people at work – employers, employees and the self-employed – are taking all necessary measures for their own and others’ health and safety.”

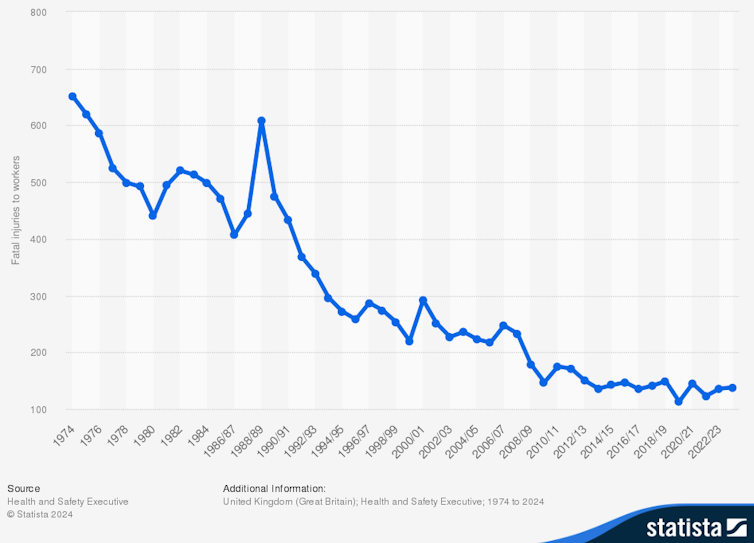

Since the act’s inception, the number of workplace deaths in Britain has fallen from nearly 650 a year in the 1960s to 135 in 2023. This decline is even more striking when considering the parallel growth in the UK workforce, from 25 million in 1974 to more than 33 million today.

Number of fatal injuries to workers in Great Britain, 1974-2024:

D Clark/statista.com, CC BY-NC-ND

Severely injured workers could now receive disability benefits or compensation funded both by the state and their employers. The act replaced the Workmen’s Compensation Act (1923), which had favoured employers, but it still placed a heavy burden on workers to prove their illness was caused by their work. As a result, the outcomes of claims varied significantly depending on individual circumstances.

Almost immediately, the act attracted criticism both for both going too far, and not far enough. In March 1975, the Daily Mail published a full page “advertorial”, issued by the Health and Safety Commission, headlined “A Great New Chance to Make Work a Lot Safer and Healthier – for everyone in Britain”. But by September, the same newspaper was mounting a scathing attack on the new Health and Safety Executive (HSE) under the headline “The Great Red Tape Plague”, which ended with a quote from an employer saying: “New rules are made so fast these days that it takes me all my time to enforce them. I’m seriously considering giving up.”

The HSE, a largely bureaucratic body, quickly introduced an increasingly complicated system of checks and balances through which employers were questioned by inspectors in order to protect workers – a system that, in time, the act became heavily criticised for.

High-profile cases of seemingly trivial bans or extreme precautions – such as forbidding conker games without goggles in schools and cancelling local traditions over liability fears – were often ridiculed in the media and by critics of bureaucracy, who framed them as evidence of a creeping “nanny state” culture that stifled common sense and personal responsibility. This extended to public health campaigns such as the push for mandatory seatbelt-wearing, which caused the Daily Mail to quip in 1977: “Those who want to enslave us all, to the Left …”

The “nanny state” criticism stuck, and has become lodged in our popular culture. Decades later, Conservative employment minister Chris Grayling compiled a list of the top ten “most bizarre health and safety bans”. Top of his list of examples of “health and safety gone mad” was an incident in which Wimbledon tennis officials cited health and safety concerns as the reason for closing the grassy spectator hill, Murray Mount, when it was wet. Grayling complained:

“We have seen an epidemic of excuses wrongly citing health and safety as a reason to prevent people from doing pretty harmless things with only very minor risks attached.”

Terms like nanny state, woke and cancel culture are now used interchangeably to criticise perceived over-sensitivity, entitlement, or self-serving and inauthentic forms of activism. In November 2024, the GB News website published an article referring to the installation of safety warnings on staircases at Cambridge University as “utter woke gibberish!”

But defenders of health and safety point out that many of these examples are, in fact, misinterpretations of the act, driven more by organisations’ fears of litigation than by government regulation. In the wake of Grayling’s top ten list, Channel 4 debunked the claims about sponge footballs and banned sack races, noting that such stories were rarely linked to the act itself.

The tension between necessary protections and perceived overreach has become emblematic of broader debates about state intervention, responsibility and risk in modern Britain. In June 2024, a survey of more than 1,200 frontline workers across six sectors found that seven in ten workers think regulations slow them down. Yet more than half (56%) agreed that they had risked their health and safety at work, with a quarter (27%) having done so “several times”.

The rise of the gig economy

The Health and Safety at Work Act, though updated several times – and with a new amendment on violence and harassment in the workplace) now being debated – is continually tested by the emergence of new types of job and ways of working.

The rise of gig work, automation, and precarious contracts has complicated traditional notions of workplace safety. The gig or freelance economy has created a culture of temporary unaffiliated workers ranging from cleaners to academic tutors to e-bike riding deliveries. These workers typically lack any form of occupational health support. Sick days mean lost wages and potential loss of jobs in the future.

During the COVID pandemic, a survey of 18,317 people in Japan found that gig workers had a significantly higher incident rate of minor occupational and activity-limiting injury, compared with their non-gig working counterparts.

A big question for regulators such as the HSE to tackle is around responsibility. Since gig workers are regarded as self-employed, they typically bear the health and safety responsibility for themselves and anyone who is affected by their work, rather than their employer. In the UK, their rights were somewhat strengthened by a 2020 high court ruling that found the government had failed to implement EU health and safety protections for temporary (gig) workers.

Health and safety legislation has been made even more complex by the adoption of new technologies and, now, artificial intelligence. In 1974, when the UK act was introduced, computers were very much in their infancy, whereas in 2024, millions of workers have exchanged desk dependency for the apparent freedom to work anywhere through phones, tablets and computers.

A particular issue for the UK government (and all sectors of the economy) is why so many people, particularly older workers, are inactive due to long-term sickness. Not only is this bad for business, it’s bad for society too. Waddell and Bell’s influential 2008 report, Is Work Good for your Health and Wellbeing?, made the case that the risks of being out of work were far higher than the risks being in work.

A growing body of evidence suggests health interventions should go beyond the remit of the original act by engaging with workers more holistically, both within and outside traditional workplaces, to help them stay in work. One intervention tested by our Healthy Working Lives Group found that sickness absence could be reduced by a fifth when a telephone-based support programme for recovery was introduced for workers who were off sick.

The modern flexibility of working locations has blurred the boundaries between work and private spheres in ways that can create additional stress and health risks – for example, for workers who never fully stop working thanks to email tethers. This is the world of work which future versions of the act must address.

My grandfather’s legacy

My grandfather died in November 2003 when I was 19, so my reflections on why he made health and safety his life’s work come in part from unpublished papers I found after his death, as well as Hansard’s reports of his robust debates in the House of Commons. For him, it was a moral imperative – demonstrated by the fact that he continued to challenge the very act he had helped create, critiquing it for not doing enough to protect workers.

Walker’s regrets over the act were poignantly revealed in December 2002, in one of his last contributions to the House of Lords before his death, when he drew from his pre-politics experiences to challenge calls to ease regulations on asbestos at work:

“I have asbestos on my chest – for most of my adult life prior to entering parliament in the 1960s, I worked in industry with asbestos, mostly white asbestos. In the 1960s, when I was a junior minister, I was involved in the discussion of the regulations relating to asbestos. The debate so far today has carried echoes of [those] discussions, when I was persuaded we should not legislate as rigorously as we might have done because the dangers had not been fully assessed. Are we going down that road again?”

Perhaps predictably, tributes after my grandfather’s death reflected the curious confusion that his health and safety legislation had aroused in British society. Labour MP Tam Dalyell praised him as “the most effective champion of workplace safety in modern British history”. In contrast, parliamentary journalist Quentin Letts ranked him 46th among people to have “buggered up Britain” – he was demoted to 53rd in Letts’s subsequent book – as the architect of a regulatory system that destroyed the industries it sought to protect. In his obituary, Letts wrote:

“Harold Walker, the grandfather of the HSE, often meant well. But that is not quite the same as saying that he achieved good things. Not the same thing at all.”

My grandfather would have been the first to argue that the act was not perfect, because compromise does not lend itself to perfection. But as I see in my research today, it changed the world of work and health by shining a critical light on workers and employers. In many ways, it led the charge for workers safety – the European Framework Directive on Safety and Health at Work was only adopted much later, in 1989.

Were he still alive, I think he would agree with Letts about some of the unintended consequences of the act. But I also think he would give short shrift to modern debates about the nanny state and wokish over-interference – dismissing these as “folk whinging”, accompanied by a characteristic roll of his eyes.

My grandfather believed his legislation was not merely about compliance, but about fostering a culture where safety became systemic and instinctive. Tales of “health and safety gone mad” have obscured his act’s true purpose – to change how we all think about our responsibilities to one another. I hope we are not losing sight of that.

For you: more from our Insights series:

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.

![]()

Simon Harold Walker does not work for, consult, own shares in or receive funding from any company or organisation that would benefit from this article, and has disclosed no relevant affiliations beyond their academic appointment.