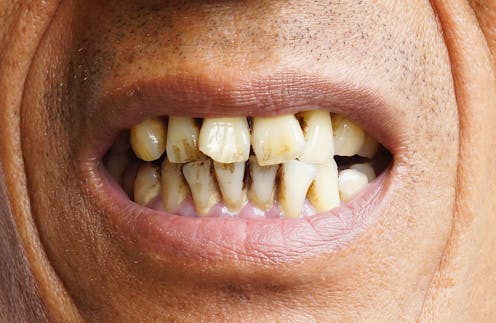

wk1003mike/Shutterstock

Images of a long line of desperate people queuing around the block in the hope of getting on the list at a new dental practice in Bristol paint a bleak picture of the state of NHS dentistry.

The situation got so desperate that police were called to provide crowd control in a scene more typical of a Taylor Swift concert than a dental waiting room. This unprecedented demand is due to a shortage of dentists in the UK, particularly ones who are willing to work for the NHS.

There may be a record number of dentists on the General Dental Council (GDC) register – over 44,000 at the start of 2024 – yet a workforce shortage is still considered a major contributing factor in the lack of dental access in the UK.

Registration figures can be misleading. Although the number of dentists in the UK is increasing, there are 1,100 fewer doing NHS work than before the pandemic, the lowest since 2012. These figures do not take into consideration changing work patterns within the dental profession, which indicate that younger dentists are working fewer clinical hours and less time within the NHS.

It is worth noting that the UK has lower numbers of dentists per head of population compared with many other European countries. The UK has 5.3 dentists per 10,000 of the population compared with 6.5 in France, 8.3 in Italy and 8.5 in Germany.

The shortage of dentists, and other dental care professionals, has finally been recognised by the government, with a NHS long-term workforce plan setting out clear goals to increase the number of training places for dentists, hygienists and dental therapists.

The government aims to increase dental training places in the UK by 40% by 2031-32, with 1,100 UK dentists qualifying each year.

Dentistry is a five-year university programme. Following that, graduates need to work for a minimum of one year as a dental foundation trainee before they are allowed to work independently as a general dental practitioner in the NHS. As a result, any increase in training places will take more than a decade to have a significant effect.

The workforce plan will offer little in the way of solace to the millions of people who currently cannot find a dentist. Urgent action is needed to avoid lengthening queues, and the government appears to have identified overseas graduates as a potential answer to their problems.

Thirty per cent of dentists on the GDC register qualified outside the UK, and in 2022, 46% of new dentists joining the register were international dental graduates.

The process of obtaining registration for international dental graduates is difficult, expensive and inefficient. It can take several years to pass the necessary exams and obtain UK registration. During that time applicants are unable to work as a dentist.

The situation is compounded by a limited number of examination places each year and a low pass rate for the practical exam (45%).

The GDC has announced an increase in exam capacity, which will allow more dentists to take the overseas registration exams. This is a practical approach to increase capacity while safeguarding standards.

No need to pass UK exam

The government has just announced a further development: the introduction of provisional registration, aimed at accelerating the registration process and allowing international dental graduates to work as a dentist without having to pass a UK examination.

This has already caused concern within the dental profession, with some commentators fearful that patient safety will be sacrificed in a race to increase dentist numbers and improve NHS access.

This view is clearly not shared by the GDC who have been quick to welcome the introduction of provisional registration.

The GDC has a responsibility to ensure that any dental professional joining the dental register has undergone the appropriate training, is capable of providing a high standard of patient care, and is fully aware of their responsibilities as a dental registrant.

The NHS is a complex system, and the current NHS dental contract and regulations are complicated and confusing. UK graduates often struggle to comprehend the nuances of the NHS, and international dental graduates will need support to ensure they are able to integrate into a new system.

Training and mentorship are important considerations. This will be a critical aspect of integrating overseas dentists into the NHS and ensuring the highest standards of care are maintained. This cannot be done without the support of the existing primary care workforce, and consideration must be given to how this is going to be delivered and resourced.

Patient safety

International dental graduates are an important part of the solution to the current workforce shortage, and a review of the present registration process was certainly long overdue. There is huge potential to use an overseas workforce more effectively, but we must ensure that patient safety remains paramount.

We must also reflect on the ethical implications of recruiting dentists from another country while considering the fairness and appropriateness of introducing international dental graduates into a widely criticised NHS system. Sustainability and continuity are valuable assets in healthcare, and the creation of a two-tier system delivered by an itinerant workforce must be avoided at all costs.

Simplifying the recruitment of overseas dentists will not save NHS dentistry alone. The problems run much deeper than a simple workforce shortage. There needs to be an honest discussion with the public, the profession and politicians about NHS dentistry. What do we want? What do we need? And what can we afford? There is no merit in recruiting more dentists if there is no commitment to address the reason so many of the workforce are leaving the NHS.

![]()

Ian Mills is affiliated with:

Member of British Dental Association

Past Dean of the Faculty of General Dental Practice of Royal College of Surgeons of England

Fellow of College of General Dentistry