The heat dome that descended upon the Pacific Northwest in late June 2021 met a population radically unprepared for it.

Almost two-thirds of households earning US$50,000 or less and 70% of rented houses in Washington’s King, Pierce and Snohomish counties had no air conditioning. In Spokane, nearly one-quarter of survey respondents didn’t have in-home air conditioning, and among those who did, 1 in 5 faced significant, often financial, barriers to using it.

Imagine having no way to cool your home as temperatures spiked to 108 degrees Fahrenheit (43 Celsius), and 120 F (49 C) in some places. People in urban heat islands – areas with few trees and lots of asphalt and concrete that can absorb and radiate heat – saw temperatures as much as 14 F (7.8 C) higher than that.

Extreme heat disasters like this are becoming increasingly common in regions where high heat used to be rare. Blackouts during severe heat waves can also leave residents who believe they are protected because they have in home air conditioners at unexpected risk. To prepare, cities, neighborhoods, companies and individuals can take steps now that can reduce the harm.

AP Photo/John Froschauer

In a new report, written with colleagues at universities and the Washington State Department of Health and released ahead of the two-year anniversary of the heat wave, we show how municipal planning agencies, parks departments, local health agencies, community-based organizations like churches and nonprofits, multiple state agencies, hospitals, public health professionals and emergency response personnel, as well as individuals and families, can play a vital role in reducing risk.

The 2021 heat dome was Washington’s deadliest weather disaster on record. It contributed to 441 deaths in the state between June 27 and July 3, our research shows. Medical systems were overwhelmed.

There are numerous ways to avoid this deadly of an outcome in the future. Many emerge from thinking about extreme heat as long-term risk reduction, not just short-term emergency response.

Table of Contents

Designing environments for cooling

Greening the urban environment can reduce heat exposure and save lives. For example, planting trees and building shade structures where people are most exposed to heat can provide local relief from extreme temperatures. That includes providing shade at buildings without air conditioning and exposed public spaces, such as bus stops and parks.

Planting rooftops with vegetation, known as green roofs, or painting them white so they reflect heat rather than absorb it, can also lower roof temperatures by tens of degrees. Used widely, they can reduce an entire neighborhood’s heat island effect by several degrees.

Climate Impacts Group/University of Washington, adapted from EPA

Efforts like these, along with tree planting campaigns in public parks and rights of way, and ordinances requiring shade trees for parking lots and private development projects, can transform the urban heat landscape.

Reaching vulnerable people

When heat waves are coming, culturally nuanced outreach efforts focused on the most vulnerable populations – and involving sources they trust – can save lives.

Government heat advisories in traditional media like radio, newspapers, TV and the internet have been shown to have limited success in changing people’s behavior. In the 2022 Spokane survey, 88% of respondents indicated they were unlikely to leave their home during an extreme heat event to go to a cooling center, for example. The reasons varied, including misperception of personal risk, fear of leaving homes unoccupied, not wanting to leave pets behind and mistrust of government.

Culturally specific resources led by community-based organizations can get around the government trust issue and can be tailored to the local population.

Alisha Jucevic for The Washington Post via Getty Images

That might mean opening cooling centers in churches or common community gathering places and launching heat awareness campaigns driven by trusted community messengers. New York City developed a door-to-door wellness check program that uses neighborhood volunteers to check on elderly and other at-risk residents.

Under this model, churches, libraries, community centers and community nonprofits take center stage, supported with resources from local and state governments. Baltimore developed more than a dozen “resiliency hubs” using this model to provide water, cooling, power for charging devices and other support.

Community-based organizations can also direct energy assistance to lower-income community members. In Spokane, one community organization created a “cooling fund” to provide portable air conditioners to those who cannot afford one.

Our report lays out many other strategies to achieve long-term heat risk reduction.

Landlords, employers and utilities have a role

Addressing extreme heat over the long term requires the participation of many other groups not tasked with protecting public health.

For example, landlords of multifamily housing and rental homes have an important role to play. After the 2021 heat wave, Oregon passed a law prohibiting landlords from restricting tenants’ ability to install window air conditioners.

Employers of people who work outdoors, or indoors in buildings without air conditioning, can protect workers by allowing more breaks, providing shade and water and adjusting work hours to avoid heat exposure – although concerns persist about rule enforcement and reduced pay.

Jahi Chikwendiu/The Washington Post via Getty Images

Utilities can make a difference by ensuring the power stays on during high-demand periods, particularly in vulnerable neighborhoods, and working with communities to reduce costs for vulnerable people that may prevent them from using air conditioning.

Ultimately, reducing extreme heat vulnerability through multiple strategies is crucial because lives are at stake.

Coordination is essential

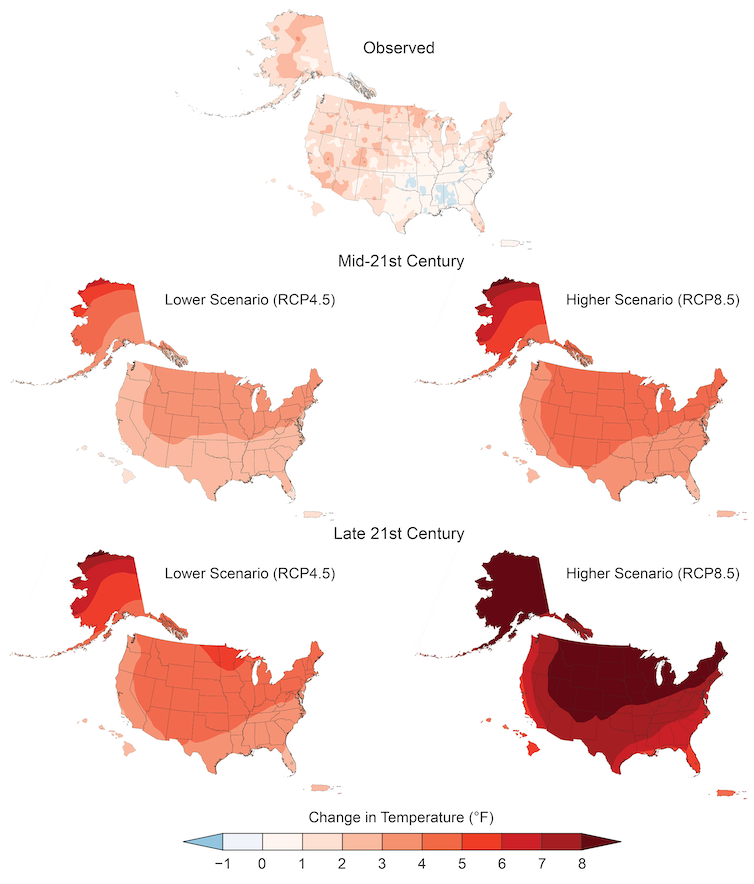

Extreme heat waves are forecast to occur more frequently across the globe as greenhouse gas emissions continue to warm the climate. Between 1971 and 2021, Washington state experienced an average of three extreme heat days per year. By the 2050s, climate models project that will rise to between 17 and 30 extreme heat days per year – a fivefold increase.

Fourth National Climate Assessment/NOAA NCEI/CICS-NC

In the end, saving lives from extreme heat is a complicated challenge requiring coordination across multiple levels of government, agencies and the civic and private sectors.

Some cities, including Phoenix, are experimenting with heat offices tasked with this coordination. But individuals have an important role to play as well.

In addition to knowing how to protect themselves, their loved ones and their neighbors, individuals can add their voices to the rising chorus calling on all levels of government and the private and civic sectors to take urgent steps to reduce heat risk.

![]()

Jason Vogel receives funding from Washington state that supports the University of Washington’s Climate Impacts Group to conduct data modeling and provide technical assistance on climate impact analysis to Washington communities, businesses, and governments.

Brian G. Henning receives funding from Gonzaga Center for Climate, Society, and the Environment to support teaching, scholarship, consulting, and capacity building.