Over 3 million people – half of them children – have now fled Ukraine because of the Russian invasion, according to the UN. This number is estimated to rise to 7 million.

The refugee crisis triggered by the Russian invasion is a vast human catastrophe. But as well as providing them with safety, food and shelter, countries in Europe receiving refugees should also ensure that people fleeing the war – especially children and young adults – are offered essential vaccines.

Vaccination rates in Ukraine have been low in recent years, due to an underfunded and struggling healthcare system. There has also been a high degree of vaccine scepticism among the Ukrainian public. A Wellcome Trust study found that only 50% of Ukrainians believe that vaccines are effective.

When people are on the move, there is an increased risk of infectious diseases, especially in reception centres and camps. The World Health Organization (WHO) is working with countries in Europe to strengthen disease surveillance (monitoring the spread of disease) and ensure immunisation services are provided.

But more can be done, including ramping up the EU’s plan to buy and distribute vaccines and speed up the emergency vaccination programme, including information campaigns, targeted at Ukrainian refugees.

These measures are urgent during the ongoing COVID pandemic, but are equally important to protect people from highly transmittable and serious diseases, such as polio and measles. This is especially the case for those under six years old, as they might have missed routine vaccinations or not know which vaccinations they have had. There is the added complication that vaccination schedules can vary from country to country. So making sure people get the right vaccines at the right intervals can be tricky.

Refugees must not be constrained by their status and should have fair access to health services. For example, vaccination registration should not collect information on migration status and share it with immigration authorities. And healthcare providers in receiving countries need to provide clear information – in a language understood by the refugees – about the recommended vaccines, their benefits, how to get them, and their possible side-effects.

Potential outbreaks

In 2002, Europe was declared polio-free. But at the end of 2021, a 17-month-old girl in western Ukraine was confirmed by the WHO to have been stricken with polio. Even though the oral polio vaccine has almost resulted in worldwide polio eradication, in communities with low vaccination rates, polio can still spread from one unvaccinated child to another.

Overall vaccination coverage for polio in Ukraine was 80% in 2021 (in Europe as a whole, this was 94%), but coverage varies across the country by age group and region. In some regions, coverage has even been as low as 60% and poses a risk for international spread through mass population movements.

After Europe has been polio-free for several decades, the progress that relegated endemic disease to just two countries in the world (wild polio, the most common form of poliovirus, still circulates in Afghanistan and Pakistan) could now be reversed.

It’s a similar story for measles. Measles presents a serious health concern, with coverage in Ukraine for two doses at 82% in 2020. Unfortunately, this isn’t enough to prevent outbreaks, and the risk is increased as some countries in Europe also have sub-optimal measles vaccine coverage, including the UK, which lost its measles-free status in 2019.

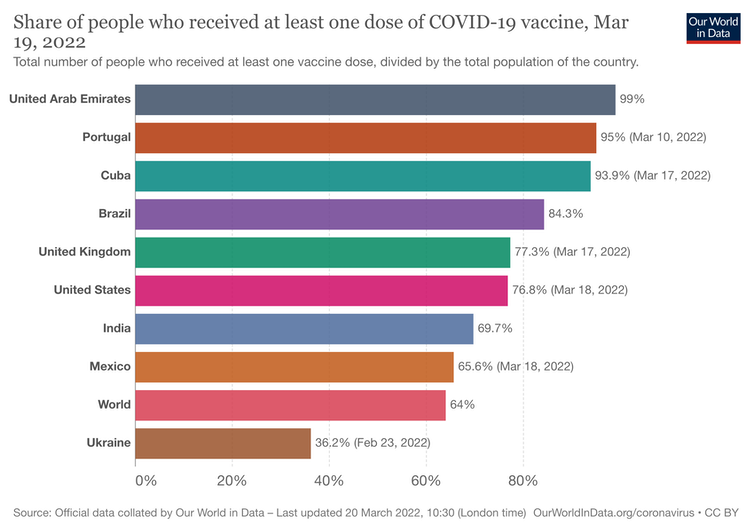

On top of this, Ukraine has been struggling to control COVID. The country has one of the lowest COVID vaccination rates in Europe. At the time of the Russian invasion at the end of February, only 36% of the population had been vaccinated. The pandemic has exacerbated pressures on the healthcare system, but rather poignantly, a national vaccination campaign had begun on February 1 2022, which was then disrupted by the war.

Our World in Data, CC BY

The significant worry now is that conflict, displacement, and the shocking humanitarian catastrophe that is happening mean that vaccination and other essential health services will continue to be severely disrupted and the conditions that cause disease will worsen.

Public health commentators have been calling for vaccination services to be provided for refugees. Even though many of the countries receiving Ukrainian refugees offer child and adult vaccination services to varying extents, this should be coordinated as a dedicated programme, with measures put in place to ensure essential vaccines are received.

![]()

Samantha Vanderslott receives funding from the IRC-AHRC.