Health passports were developed to help patients better communicate their needs with medical staff by allowing people to record details about their disability or health condition. They are sometimes known as a communication passport, healthcare passport or a hospital passport and can be digital or on paper.

Autism health passports were specifically designed with the aim of achieving more equitable access to healthcare for autistic people. But how effectively do they achieve this?

We reviewed the evidence to see if they met their aims. The literature we found tended to focus on describing the passports rather than evaluating their effectiveness.

Around 3% of the population is estimated to be autistic and autistic people experience the world differently. We have sensory, social and communication differences. We also often have co-occurring conditions such as hypermobility, epilepsy and ADHD.

The Equality Act of 2010 states that government services – including healthcare – have a duty to provide “reasonable adjustments” for autistic people. This means organisations must make changes to how they provide their services to remove any social or environmental barriers.

Despite this, health services are often less accessible for autistic people. This is because such environments can include bright lights and lots of background noise which may cause physical pain and brain fog. Also, health professionals don’t always understand enough about autism to know how to communicate effectively with autistic patients.

This can lead to negative experiences and even early death for autistic people. Autistic people have reported concerns about being misunderstood or facing discrimination when they ask for medical support.

Autism health passports were introduced to overcome such challenges. For example, the “my health passport” was developed in the UK in 2014 by Baroness Angela Browning in collaboration with the National Autistic Society. There are other autism health passports from different organisations too.

Health passports have been endorsed by the UK government, which is responsible for health in England. Using a health passport is also recommended as best practice by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence.

Our review identified all studies from across the globe which focused on autism health passports for people over the age of 16. We identified 13 sources in our review, of mixed quality. Four of which were not empirical and four were based in the UK.

We discovered that almost no information exists about whether autism health passports have achieved their aims. The studies we reviewed included information about the contents of the health passports, such as the person’s name, date of birth and communication needs.

But they did not say how they were supposed to be used in appointments, or include information such as who should fill out the passport, for example. What’s more, most of them did not test if the passports were effective.

For this reason, it is not possible to determine whether autism health passports help autistic people better access healthcare.

Barriers

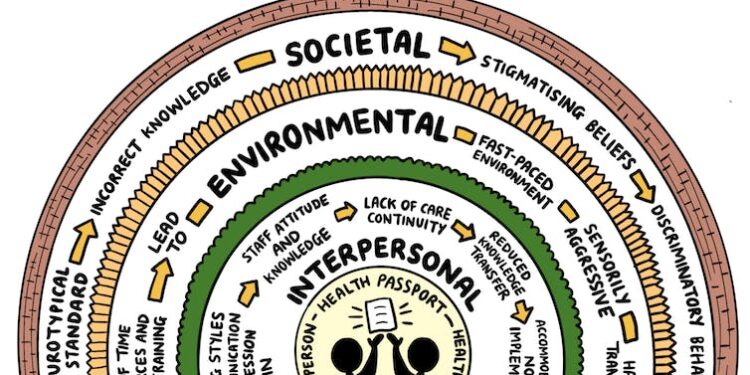

Besides, there are already many societal, environmental and interpersonal barriers which prevent autism health passports from working effectively.

The general understanding of autism in society tends to be outdated, often limited to viewing it as a medical condition. Non-autistic brains are often considered as “the norm” while other types of brains can be viewed negatively by the general population.

Viewing autism as a medical condition can stigmatise autistic people and impacts how many non-autistic people – including health professionals – engage with autistic people.

Many autistic people prefer the social model of disability instead. This states that society creates disability through a range of barriers that could be, but are not, removed. Autism is also an important part of some autistic people’s identity.

Rebecca Ellis, Author provided

Staff who have not received autism training may be unaware of the adaptations needed to make healthcare more accessible. They may also not be aware of the co-occurring conditions that are often present alongside autism.

And due to staff and resource shortages, even with good knowledge of autism, health professionals may not have time to read additional materials such as an autism health passport.

How to make positive changes

Environmental changes are needed to provide better care for autistic people, because hospitals can be fast-paced and overwhelming places. Patients may have to move between areas of a large, often confusing, building and work with a number of different professionals, with varying levels of neurodiversity-affirming training.

This situation could be improved by using quiet spaces and assigning appropriately trained key workers to autistic patients. We do not think that “bolt on” tools like autism health passports are enough to create meaningful change in otherwise inaccessible health services.

A service redesign is necessary to meet autistic needs. Whether or not a tool such as a health passport can positively influence an autistic person’s experiences of healthcare is dependent on making wider changes to services.

Such initiatives should also be co-designed with autistic people to give them the greatest chance of being effective. By improving services in this way, they could meet the needs of other marginalised groups too.

![]()

Rebecca Ellis received Health and Care Research Wales funding for their PhD.

Aimee Grant receives funding from the Wellcome Trust, the Medical Research Council and the Research Wales Innovation Fund (part of HEFCW).