Walk into any blood donation center in the United States and you’ll see the same posters saying “Every two seconds, someone needs blood.” What those signs don’t say is that the people who need it most often come from the same communities least represented in the donor pool. Black Americans make up roughly 13% of the U.S. population yet account for less than 3% of blood donors, according to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI). It’s a mismatch with real consequences for patients who rely on racially or ethnically matched blood.

Table of Contents

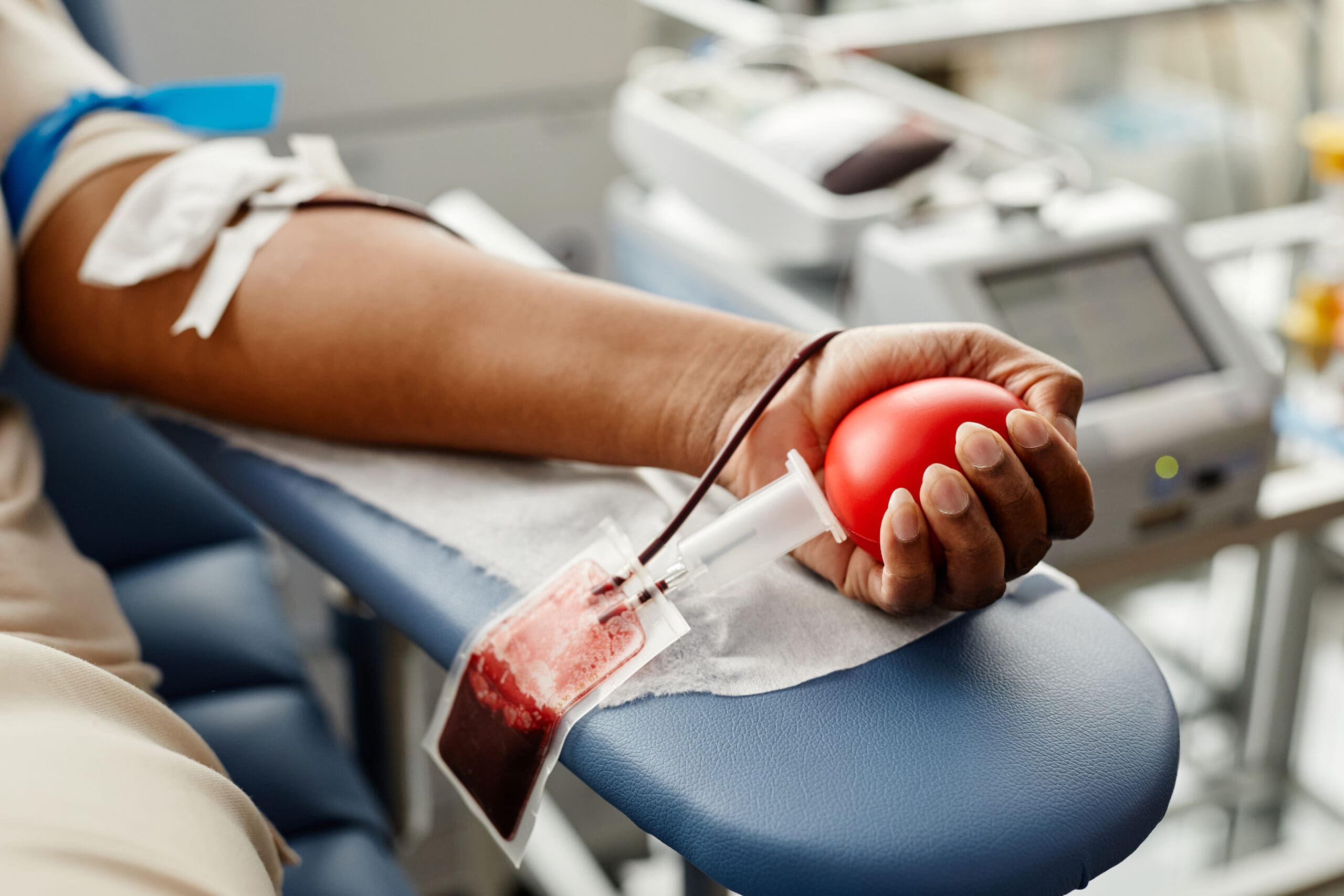

Why Our Donations Matter So Much

For many of us, the people behind these numbers are not hypothetical. They are our children, our siblings, our neighbors living with sickle cell disease. According to the CDC, sickle cell affects more than 100,000 people in the United States and more than 90 percent of those affected are Black.

When the donor pool does not reflect our community, the people we love feel the impact first. According to Kaiser Permanente, blood transfusions can treat severe complications of sickle cell disease and help prevent additional problems, including lowering the risk of stroke in children. The safest matches often come from donors with similar genetic markers. As noted by the American Red Cross, this includes rare blood types such as U-negative and Duffy negative, which are found mostly among people of African descent.

The Hesitation Around Donation

In 2023, the NHLBI spoke with Black adults across the country to learn how they think and feel about blood donation. The conversations were honest and familiar. People named the history that still shapes their choices, including the segregation of blood supplies and the sense that donation drives rarely show up in Black neighborhoods or center Black experiences.

Researchers held twelve focus groups with adults ages 18 to 50. Some had donated once. Others had never donated but were open to it. Younger participants tended to know more about the process. Older participants often felt they did not have enough information to feel confident. Across every group, people said convenience, representation, and trust mattered.

Participants wanted to see blood drives in places they already go. They wanted clear information from trusted Black medical professionals. And they wanted to understand who their blood would help. Sickle cell disease affects more than 100,000 people in the United States, most of whom are Black, and many rely on transfusions throughout their lives. One in three Black donors is a match for someone living with sickle cell. Some rare blood types, including U-negative and Duffy negative, are found almost entirely in the African American community. A diverse blood supply is essential for patients who need those matches.

The message from the focus groups was simple. People want a donation experience that feels honest and connected to their lives.

Building a Donation Experience That Works

The NHLBI research makes one thing clear. When Black communities receive information that feels trustworthy, relevant, and grounded in their lived experience, willingness to donate rises. Change begins with meeting people where they are.

Convenience matters. Donation sites placed in familiar community spaces such as churches, malls, recreation centers, barbershops, and neighborhood hubs can remove a major barrier. Many participants said they would be more open to donating if the process felt easy to access or if they had someone to go with them. Compensation, even something modest like food or a small incentive, was also named as a meaningful motivator.

Trusted messengers matter just as much. Participants wanted clear information from Black medical professionals who could explain the process, address myths, and show the real impact of donation. They also wanted to understand exactly who their blood would help. Stories of patients living with sickle cell disease, families navigating weekly transfusions, or community members relying on rare blood types can create a sense of connection that national messaging often misses.

Helping others remains the strongest motivator. Many participants described the emotional pull of knowing their donation could save a life or support someone in crisis. When that impact is visible and personal, hesitation shifts toward action.

Building a more diverse blood supply is possible. It starts with information that feels honest, spaces that feel familiar, and outreach that reflects the communities it hopes to serve.

This Is About Health Equity

The shortage of Black blood donors reflects gaps in access and trust, shaped by a long history that has given our community real reasons to question the medical system. That history still leaves many people without the information or reassurance they need to feel confident about donating. It’s a health equity issue.

It’s also a place where meaningful progress is possible. When Black donors give blood, they strengthen a safety net that protects their own families and communities. They help a child with sickle cell get the match they need. They fill a gap that only this community can fill.

This moment can be a turning point. Not because the system has suddenly changed entirely, but because Black patients deserve the security that comes with a reliable and diverse blood supply.

Showing up for one another has always been a source of strength, and this year may be the year that strength reaches the donation room.

Resources:

How Black Americans Can Save Lives by Donating Blood

Blood Transfusions for Sickle Cell Disease | Kaiser Permanente